Mario is Missing! (Nintendo Entertainment System): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary Tag: Mobile edit |

(→Mistakes and errors: Added extra information as to where the 800 year statement comes from.) |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

*A boy states that China is the largest country in Asia, even though {{wp|Russia}} has the most territory (without even including its territory in Europe).<ref>{{cite|author=Pariona, Amber|title="Which Are the 10 Largest Asian Countries By Area?"|publisher=WorldAtlas|date=November 3, 2017|url=www.worldatlas.com/articles/which-are-the-10-largest-asian-countries-by-area.html}}</ref> | *A boy states that China is the largest country in Asia, even though {{wp|Russia}} has the most territory (without even including its territory in Europe).<ref>{{cite|author=Pariona, Amber|title="Which Are the 10 Largest Asian Countries By Area?"|publisher=WorldAtlas|date=November 3, 2017|url=www.worldatlas.com/articles/which-are-the-10-largest-asian-countries-by-area.html}}</ref> | ||

*A reporter states that Beijing has been the capital of China for 800 years. However, the timeline does not work out: considering that Beijing was officially made the capital in 1279,<ref>{{cite|author=Wang, Yi|title="Dadu in the Yuan Dynasty" - ''A Century of Change: Beijing's Urban Structure in the 20th Century'', illustrated ed.|publisher=Springer International Publishing|date=July 20, 2016|isbn=978-3319396330|page=14|url=books.google.ca/books?id=RRq1DAAAQBAJ|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> just above 700 years would have passed by the time of ''Mario is Missing!''{{'}}s release. This also ignores the two gaps in which Beijing was not China's capital: from 1368 to 1420, when {{wp|Nanjing}} was made the capital during the {{wp|Ming dynasty}},<ref>{{cite|author=Fang, Jun|title=''China's Second Capital – Nanjing under the Ming'', 1368-1644|publisher=Routledge|date=May 23, 2014|url=books.google.ca/books?id=f1uhAwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-1135008444|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> and from 1928 to 1949, after the {{wp|Chinese reunification (1928)|1928 Chinese reunification}} and numerous other events until the formation of the People's Republic of China. | *A reporter states that Beijing has been the capital of China for 800 years. However, the timeline does not work out: considering that Beijing was officially made the capital in 1279,<ref>{{cite|author=Wang, Yi|title="Dadu in the Yuan Dynasty" - ''A Century of Change: Beijing's Urban Structure in the 20th Century'', illustrated ed.|publisher=Springer International Publishing|date=July 20, 2016|isbn=978-3319396330|page=14|url=books.google.ca/books?id=RRq1DAAAQBAJ|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> just above 700 years would have passed by the time of ''Mario is Missing!''{{'}}s release. This also ignores the two gaps in which Beijing was not China's capital: from 1368 to 1420, when {{wp|Nanjing}} was made the capital during the {{wp|Ming dynasty}},<ref>{{cite|author=Fang, Jun|title=''China's Second Capital – Nanjing under the Ming'', 1368-1644|publisher=Routledge|date=May 23, 2014|url=books.google.ca/books?id=f1uhAwAAQBAJ|isbn=978-1135008444|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> and from 1928 to 1949, after the {{wp|Chinese reunification (1928)|1928 Chinese reunification}} and numerous other events until the formation of the People's Republic of China. | ||

** The statement could be an incorrect quote of a Chinese saying that describes Beijing as a 3,000 year old city that has served as a capital for 800 years.<ref>北京三千年,定都八百载</ref>. This saying refers to {{wp|Zhongdu}}, the capital city of the {{wp|Jin_dynasty_(1115–1234)|Jin dynasty}} established in 1153 in modern-day Beijing. <ref>http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/beijing/30785.htm</ref> | |||

*A boy says that the [[Gate of Heavenly Peace]] leads to the Emperor's home in the [[Forbidden City]], which is misleading: the Forbidden City itself was the Emperor's home. | *A boy says that the [[Gate of Heavenly Peace]] leads to the Emperor's home in the [[Forbidden City]], which is misleading: the Forbidden City itself was the Emperor's home. | ||

*A scientist says that the gate was created in the fourth century, while the Forbidden City's pamphlet says that it was built in 1651. Both of these are incorrect: the gate was built in 1417,<ref name="eBeijing Tiananmen Gate">{{cite|title="People's Daily Online" - "The History of Tiananmen Gate"|publisher=eBeijing|date=November 26, 2010|url=www.ebeijing.gov.cn/BeijingInformation/BeijingsHistory/t1141051.htm|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> although it was rebuilt in 1651 after being burned down.<ref>{{cite|title="Tian'anmen -- the Gate of Heavenly Peace"|publisher=China.org.cn, China Internet Information Center|url=www.china.org.cn/english/features/beijing/30801.htm|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> | *A scientist says that the gate was created in the fourth century, while the Forbidden City's pamphlet says that it was built in 1651. Both of these are incorrect: the gate was built in 1417,<ref name="eBeijing Tiananmen Gate">{{cite|title="People's Daily Online" - "The History of Tiananmen Gate"|publisher=eBeijing|date=November 26, 2010|url=www.ebeijing.gov.cn/BeijingInformation/BeijingsHistory/t1141051.htm|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> although it was rebuilt in 1651 after being burned down.<ref>{{cite|title="Tian'anmen -- the Gate of Heavenly Peace"|publisher=China.org.cn, China Internet Information Center|url=www.china.org.cn/english/features/beijing/30801.htm|accessdate=January 26, 2018}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:11, November 5, 2024

It has been requested that this article be rewritten. Reason: this page and its two analogues were split from the original Mario is Missing! article in a sloppy fashion. Much of the writing present in this article was simply copy-pasted from the original article with no concern as to whether it's relevant to the version of the game described here. This also results in a lot of repeat content across the three "Mario is Missing!" articles, which violates the wiki's "Once and only once" rule. Details here.

| Mario is Missing! | |||

|---|---|---|---|

For alternate box art, see the game's gallery. | |||

| Developer | The Software Toolworks Radical Entertainment | ||

| Publisher | The Software Toolworks (U.S.) Mindscape (Europe) | ||

| Platform(s) | Nintendo Entertainment System | ||

| Release date | |||

| Language(s) | English (United States) | ||

| Genre | Educational | ||

| Rating(s) |

| ||

| Mode(s) | Single player | ||

| Format | NES:

| ||

| Input | NES:

| ||

| Serial code(s) | |||

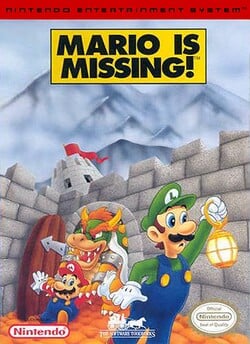

Mario is Missing! is an educational game created for the NES. It is the first game of the Mario Discovery series. Its gameplay was widely panned by critics. A follow-up called Mario's Time Machine was later released. This is the second game in the Super Mario franchise in which Luigi is the sole main protagonist, the first being Luigi's Hammer Toss. This game is mostly based on Super Mario World, which was a common theme of the Mario Discovery series and Super Mario educational games.

Story

In his latest scheme, Bowser decides to flood the Earth with hairdryers from Hafta Havit Hairdryer Hotline Corp to melt Antarctica. In order to buy the hairdryers, Bowser has his Koopas travel all over the world and steal various important landmarks he plans to sell. Mario, Luigi, and Yoshi follow Bowser to Antarctica to stop him. However, Mario proceeds on his own and is captured by Bowser. A Koopa throws a bag over Mario as he is fuming about the game's title claiming he is missing as he walks through the ice and snow.

With Mario captured, Luigi finds himself faced with the task of returning all the stolen artifacts and saving both his brother and Earth. He bravely enters the castle, leaving Yoshi outside.

Story from console instruction booklet

Bowser's Plot

Oh no! Bowser and his bad boys are back to a life of crime. This time, it's not Mario World — it's your world! From his Antarctic castle, Bowser hustles his cold-blooded crew of cantankerous Koopas into his powerful Passcode Operated Remote Transport And Larceny System (PORTALS). The twisted turtles transport themselves throughout the globe, where celebrated cities suffer shell-shocking crime waves, as turtles trash landmarks and loot ancient artifacts. With dough from his slimy scales, Bowser hoards hair dryers from the Hafta-Havit Hotline. His plot? Melt Antarctica and flood the planet! Whoa!

Mario's Fate

Will the brave brothers from Brooklyn permit this abominable snow plan? The boys say "Not!" Mario, Luigi and Yoshi trek across ice and snow to shellac the shelled ones' schemes. But Bowser's slick; in one last trick, he takes the dearest thing of all...Mario is Missing!

Luigi's Mission

Luigi must stop the Koopas, foil Bowser's plan, and find Mario. Sneaking into each Portal, Luigi is transported to a city in trouble. There, Luigi needs to nab each Koopa, grab its loot, and return the artifact to its proper landmark. Along the way, Luigi explores the city, chats with the locals, reads maps, and solves puzzles. Help him do this before time runs out! Once he figures out where he is on the globe,

Luigi must use the Globulator to call Yoshi. Only after Yoshi scares Pokey away, can Luigi return to Bowser's castle and lock the Portal for that city.

Ending

Luigi and Bowser have a boss battle and "Bowser" turns out to be a normal Koopa in disguise, who turns the key to Mario's cell, freeing him.

Characters

Playable

Supporting

Antagonists

Gameplay

In each level, Luigi must retrieve several artifacts which were stolen by several Koopas within the city and return them to their rightful places. Luigi must jump on the Koopas to defeat them and reclaim the artifacts, which he then takes back to the landmarks they were stolen from. He must answer trivia questions about the landmarks before the Curators will take the wares back.

As well as returning the artifacts, Luigi must also deduce what city he is in so that he can use the Globulator and call Yoshi to his aid for double the walking and running speed. Without Yoshi, Luigi cannot finish the level, as the exit pipe is occupied by a Pokey.

Once Luigi has secured all the cities whose doors are located on a floor of the castle, Luigi must engage in a small boss battle with a Koopa. However, the bosses cannot hurt Luigi, and must be stomped on a certain number of times to be defeated in the SNES and NES versions. The console versions also differ in that the Koopas are not defeated when they are knocked about and forced to leave in an undignified manner, but rather a sound stomp with destroy them upon impact (including the shell).

Cities

- First room

- New York City, New York (United States)

- Rome, Italy

- Second room

- Sydney, Australia

- San Francisco, California (United States)

- Third room

- Fourth room

- Fifth room

- London, England

- Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Sixth room

- Mexico City, Mexico

- Cairo, Egypt

- Seventh room;

Mistakes and errors

This section is under construction. Therefore, please excuse its informal appearance while it is being worked on. We hope to have it completed as soon as possible.

Although Mario is Missing! is intended to teach its players geographical facts, it contains numerous errors and oddities in its teaching material.

- General

- Some information in the game features proper terms that are not well known outside of North America. For example, the pamphlet for the Big Ben calls its subject "England's Capitol Hill"; as Capitol Hill is a metonym for the area surrounding the United States Capitol, this analogy, despite being technically correct, would likely confuse players who are unfamiliar with the metonymies used in American politics.

- Colombia's capital, Bogotá, is misspelled as "Bogata."

- Iceland's capital, Reykjavik, is spelled "Reykavik."

- Tajikistan's capital, Dushanbe, is spelled "Dashnabe."

- The largest city in New Zealand, Auckland, is spelled "Auchland."

- A boy states that China is the largest country in Asia, even though Russia has the most territory (without even including its territory in Europe).[5]

- A reporter states that Beijing has been the capital of China for 800 years. However, the timeline does not work out: considering that Beijing was officially made the capital in 1279,[6] just above 700 years would have passed by the time of Mario is Missing!'s release. This also ignores the two gaps in which Beijing was not China's capital: from 1368 to 1420, when Nanjing was made the capital during the Ming dynasty,[7] and from 1928 to 1949, after the 1928 Chinese reunification and numerous other events until the formation of the People's Republic of China.

- The statement could be an incorrect quote of a Chinese saying that describes Beijing as a 3,000 year old city that has served as a capital for 800 years.[8]. This saying refers to Zhongdu, the capital city of the Jin dynasty established in 1153 in modern-day Beijing. [9]

- A boy says that the Gate of Heavenly Peace leads to the Emperor's home in the Forbidden City, which is misleading: the Forbidden City itself was the Emperor's home.

- A scientist says that the gate was created in the fourth century, while the Forbidden City's pamphlet says that it was built in 1651. Both of these are incorrect: the gate was built in 1417,[10] although it was rebuilt in 1651 after being burned down.[11]

- The scientist also says that the reigning emperor, the Yongle Emperor, was the one who built the gate. While he ordered its construction, it was designed by Kuai Xiang in conjunction with other architects.[12]

- It is stated on several occasions that only the Emperor could pass through the Gate of Heavenly Peace, when it was actually the Gate of China that had this restriction.[10]

- It is stated on multiple occasions that the Great Wall of China is the only man-made object that is visible from space, despite this being completely false; other objects are visible from space[13][14] and the wall itself is not even visible.[15][16]

- The pamphlet states that the Great Wall is one of "the world's seven great wonders", which is misleading: the traditional list of the seven Wonders of the World does not include the Great Wall, but it is typically included in lists about the wonders of the medieval world.[17][18]

- The pamphlet also says that it took 300,000 men ten years to construct the entire Great Wall. This is incorrect for three reasons: for one, portions of the wall were built across several centuries; secondly, several hundreds of thousands,[19] if not millions,[20] of people were forced to work on the wall; finally, while 300,000 soldiers were conscripted to build one section of the wall, it took them nine years to do so.[21]

- It also states that the wall was "[b]egun in fifth century BC", despite walls being constructed many centuries prior; they were also only joined together after 221 BC.[22][better source needed]

- The pamphlet also says that it took 300,000 men ten years to construct the entire Great Wall. This is incorrect for three reasons: for one, portions of the wall were built across several centuries; secondly, several hundreds of thousands,[19] if not millions,[20] of people were forced to work on the wall; finally, while 300,000 soldiers were conscripted to build one section of the wall, it took them nine years to do so.[21]

- The building that is stolen from the Temple of Heaven is called the Hall of Good Harvest, the Good Harvest Hall, and the Great Hall in-game, none of which are actually names for it. It is officially the "Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests".[23]

- One of the questions for returning the hall involves answering what was not used during its construction; though "air conditioning" is a technically valid answer, it is not accepted for the question.

- The Mosque of Muhammad Ali is shown on the in-game map as being located on the west side of the Nile River; in actuality, it is located on the east side of the Nile.

- The pamphlet for the Big Ben states that the distinction of the tower's eponymous nickname goes to its chime bell and not the clock itself. This is both incorrect and a hypocrisy; the bell is technically a part of the clock's mechanism, and the "Big Ben" name is collectively used for both the entire clock mechanism and the Elizabeth Tower (then known as the Clock Tower).[24]

- The pamphlet for the Tower of London states that one of the main reasons William the Conqueror built the tower was to "oversee shipping" on the River Thames. While it is plausible that the pamphlet is referring to the castle's proximity to the Thames providing a militaristic advantage,[25] there is no evidence that the diplomatic use of the river is attributed to William the Conqueror, nor is there any evidence that he ever regulated commerce on the river.

- A reporter says that "Montreal is an island in the St. Lawrence River", which is misleading: the player visits the city of Montreal, which is contained within, but distinct from, the Island of Montreal.

- A scientist says that Montreal means "royal mount," which is misleading: it actually takes its name from "Mount Royal" which is a mountain located in the center of the island, in the 16th century, "Réal" was a common way of saying "Royal" in French.

- The image of the Dome looks nothing like the actual dome of Saint Joseph's Oratory (perhaps coincidentally, it resembles the Montreal Biosphère).

- A reporter suggests that the Dome is only smaller than that of the one on St. Peter's Basilica in Rome; this is very much incorrect.[26]

- A policeman mentions 158 light bulbs on the mountain, where there are actually 30 (originally 240 before being changed in 1992).[27]

- A tourist says that the Olympic Stadium seats 70,000 people; its actual max capacity is around 60,000.[28]

- A reporter says that the Tilted Tower was built for the 1974 Olympics, and not the 1976 Summer Olympics as in reality; neither the summer nor winter versions of the Olympic Games were held in 1974. Additionally, the Titled Tower is actually known as the Montréal Tower in reality.[29]

- Most NPCs act as if the Soviet Union still exists, despite the game being released well after its dissolution on December 26, 1991. The sole exception is a tourist who gripes how "First it was Russia, then the Soviet Union, now it's Russia again!" This line further introduces an inaccuracy of its own, as the Soviet Union officially acknowledged Russia as a constituent republic (one of fifteen that made up the USSR), and "Russia" was frequently used in English-language vernacular as a byword for the entire union during its lifetime.

- While a boy points out GUM's letters in the Cyrillic script, the text misspells Cyrillic as "Cyrlik".

- The largest lake in Russia is said to be the Caspian Sea. However, the Caspian Sea is not fully enclosed within Russia, but merely connected to it, and even then, the largest lake to be connected to Russia is actually the Black Sea. The largest lake to be fully enclosed within Russia is Lake Baikal.

- The height of the central structure of St. Basil's Cathedral is stated to be 107 feet; it is officially 47.5 meters tall, around 156 feet.[30]

- The term "Holy Fool" is said to mean "saint" in Russian. This is incorrect: a holy fool refers to anyone who surrenders themselves to God at the expense of themselves and societal norms, even if they are not a saint, and the concept of Foolishness for Christ appears outside of Russia, even within the Bible itself.

- The pamphlet for the cathedral says that it was built in 1555, which is misleading when it was constructed from 1555 to 1560.[31]

- It also says that it was built by "Ivan III," while also calling him Ivan the Terrible. While Ivan the Terrible did order its construction, he was "Ivan IV"; Ivan III was his grandfather.

- It also says that he ordered the cathedral built to honor Basil the Blessed. It was actually built to commemorate his recent victory in conquest; Basil's name was only attached to the building in the seventeenth century.[32] While St. Basil does have a mausoleum within the cathedral, it was only constructed in 1588.[30]

- It also says that it was built by "Ivan III," while also calling him Ivan the Terrible. While Ivan the Terrible did order its construction, he was "Ivan IV"; Ivan III was his grandfather.

- The names "Bolshoi Ballet" and "Bolshoi Theater" are used interchangeably (for example, it is stated that the Bolshoi Ballet has been closed for visitors). However, the Bolshoi Ballet is a dance troupe, whereas the Bolshoi Theater is an actual building.

- It is claimed that the Bolshoi Theater "sells out every show." This is despite a period where it struggled to gather an audience,[33] which is to say nothing of canceled shows in the past.[34]

- Its pamphlet attributes the introduction of realism to ballet with one of the Bolshoi Ballet's directors, Alexander Alexeyevich Gorsky; realism within ballet can actually be traced to the 1830s.[35]

- It also claims that Gorsky served as the director until 1942, despite him dying in 1924.[33]

- It also claims that the theater was constructed in 1856; it was actually in 1780, with restorations taking place until 1856 after a fire in 1853.[36]

- A tourist says that the Emperor's Bell weighs 210 tons. Officially, it is about 202 tons.[37]

- A reporter claims that Ivan III had the bell placed in the Ivan the Great Bell Tower. This tower has 22 bells, none of which are the Emperor's Bell; it has never once been suspended or rung.[38]

- A policewoman says that the bell has been in the Kremlin since the 17th century. It has actually been there since it was constructed in 1735 (i.e. the 18th century);[38] it was also moved to its current location in 1836.[39]

- Many of the buildings in Nairobi are old and dilapidated, with some even being held up with sticks and straw roofs; this is a far cry from the contemporary city in reality.

- A tourist said that he had to fight off lions and elephants when traveling from Mombasa to Nairobi, which is odd given that there is a highway that directly connects the two cities.

- A scientist comments that female Asian elephants cannot grow tusks, which is incorrect. Some of them have smaller tusks, called "tushes," that are notably more brittle than males' tusks, but are still present. The scientist also implies that male Asian elephants always grow tusks, which is also incorrect.[40]

- The pamphlet for the Nairobi National Park describes the area as "undisturbed", which is incorrect given the proximity of human civilization and how it interferes with the area.[41]

- The Maasai Headdress, in both its NES and SNES sprites, look nothing like the enkuraru headdresses worn by actual Maasai warriors.[42][43]

- The pamphlet for the Maasai village says that Africa has "more than 70 tribes", which is a gross understatement: estimates often place more than 3,000 tribes in Africa.[44][45]

- The pamphlet also says that new warriors are initiated as soon as they turn fifteen, but this process can begin anywhere from the ages of fourteen to eighteen.[46]

- The National Museum of Kenya's actual name is the Nairobi National Museum.[47]

- The Human Skull was discovered by Bernard Ngeneo, a member of Richard Leakey's expedition team, and not Leakey himself.[48]

- Also, unlike what the game claims, the skull depicts a member of the Homo rudolfensis species and not Homo habilis (although initial claims thought the skull to be Homo habilis, it was first classified as a new species in 1986[49]).

- King Kong is stolen from the Empire State Building and must be returned to its supposed rightful place, despite King Kong being entirely fictional, though this is mentioned in the game.

- An NPC can say, "So nice they named it twice, NY, NY." While this is colloquially acceptable, this technically refers to the borough of Manhattan specifically.

- The same NPC can say, "Catch a cab, or take the subway, not many private cars in this island city." This implies that it is on a single island when in reality the city is mostly part of an archipelago (with the main exception being the Bronx, located on the mainland). The islands are not represented on the Globulator, though the City Map and artifacts indicate that it is geographically centered around Manhattan.

- The Tricolor is stolen from the top of the Eiffel Tower, but in real life, it was never flown there to begin with.

- A boy mentions that France is the biggest country in Europe after the Soviet Union has broken up; in reality, Russia's European portion and Ukraine are each larger than France.[50]

- A tourist misspells "aéroport" as "airport" in L'Airport d'Orly.

- A business woman mentions obtaining French fries, though their origin as a French food has been disputed, with sources citing possible origins in Belgium or Spain.[51]

- A tourist uses the name "Latin Manhattan" for Rome. This has never been a nickname for the city; in fact, it is an alcoholic drink.[52] However, the nickname has been associated with Buenos Aires.[53]

- The Colosseum's pamphlet lists its circumference as 573 yards, and not 544 meters (about 594 yards) as in reality.[54]

- A scientist says that "Sistine" means six in Latin. Six in Latin is "sex" or "sextus"; "Sistine" refers to any of the Sixtus popes, although "Sixtus" is derived from "sextus".[55]

- The Sistine Chapel's pamphlet describes Michelangelo painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling's 10,000 square feet. He actually painted around 534 square meters (about 5,747 square feet).[56]

- It also describes him as having painted while lying down, which is a common misconception. He actually painted while standing up.[57]

- The Trevi Fountain's pamphlet says that anyone who throws a coin over their shoulder and into the fountain is guaranteed to return to Rome. Although technically correct, this is missing details, as the myth specifies that a person must throw a coin with their right hand over their left shoulder.[58]

- The Trevi is also said to be the oldest fountain in Rome, which is incorrect due to the Fountain in Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere.

- A scientist says that "no one" was interested in San Francisco until the California Gold Rush in 1848, which is a rather flippant statement. Although the gold rush brought droves of new people to the settlement, it still had a sizable population; it was the initially steady influx of immigrants that allowed people to explore the surrounding territory in the years leading up to the gold rush.[59]

- Despite there being multiple fog horns along the Golden Gate Bridge, only one Fog Horn appears as an item.[60]

- A boy states that the Bridge is 260 feet above the San Francisco Bay, although it is actually 220 feet above water from bridge itself and 500 feet above land from the top of the tower.[61]

- It is stated that the Bridge was built in 1937, which is misleading when construction started in 1933 and finished in 1937.[62]

- The pamphlet for the bridge says that fog covers it on "most days"; fog usually rolls over during the summer.[63]

- The Coit Tower was purportedly built in 1934; it was actually in 1933.[64]

- The Tower's pamphlet says that its namesake is "Lillian Hitchcock Coit"; her name is actually Lillie Hitchcock Coit.

- It also claims that Lillie donated $125,000 specifically to build the tower. Firstly, she donated $118,000 (although this expanded to $125,000 due to additional city funds), and she also donated the money to city for the general purpose of beautification, and not solely for the tower.[65]

- The Transamerica Pyramid is on Montgomery Street, and not Columbus Avenue as its pamphlet claims.

- Its pamphlet only mentions that it is on a concrete base, disregarding the steel that was also used.[66]

- A woman explains that "I always thought Australia's capital was spelled like "Sid's-Knee"", referring to Sydney, when in reality it is Canberra that is Australia's capital, a fact which is stated by another NPC in the game.

Gallery

- Main article: Gallery:Mario is Missing!

Quotes

- Main article: List of Mario is Missing! quotes

Pre-release and unused content

It has been requested that this article be rewritten and expanded to include more information. Reason: include information about lots of unused sprites from NES version

Reception

Steve Merrett and Robert Whitfield of Nintendo Magazine System both commend the game for succeeding in being both educational and entertaining, unlike most other educational games.[67] They also praise the variety of locations to explore and objects to collect, though they criticize that the core gameplay is a bit repetitive and the city graphics are lack-luster. While they acknowledge that Super Mario fans and older demographics may not derive much enjoyment from the game, they do recommend the game to those who have an interest in geography or under the age of eleven.

Electronic Gaming Monthly's "Review Crew" gives the game a combined average score of 5.75/10.[68] Steve Harris, Ed Semrad, and Martin Alessi all recommend the game to only young audiences and praise the educational content. However, Alessi criticizes that the game has very little challenging action sections. He points out that even boss fights "offer little to no challenge". Sushi-X, who gives the game the lowest score of 3/10, criticizes that the game plays like a slow Super Mario game and that the graphics were not lively enough to keep him interested.

Sales

In an August 1993 press release, Software Toolworks claimed that sales of the console versions of Mario is Missing! exceeded $7,000,000 for the fiscal quarter and that the game boosted the company's revenue during a slow quarter.[69] One employee also claims that the game sold over one million units.[70]

References to other games

- Super Mario World: The Mario, Luigi, and Yoshi sprites were taken from this game. Bowser's sprite appears to use an edited version of Morton, Ludwig, and Roy's body from this game, along with an edited version of Lemmy's head. As such, he is uncharacteristically short in this game. When retracted into his shell, it uses the normal Koopa Troopa shell sprite from this game, except with all original detail removed and spikes drawn on. Finally, after defeat, he is knocked out of his shell and appears as an unshelled Koopa, specifically from a Koopa Troopa. Some backgrounds in the NES version are derived from similar backgrounds in Super Mario World.

References in later games

- Nintendo World Championships: NES Edition: Mario is Missing! can be selected as the player's favorite NES game on their profile.

Staff

- Main article: List of Mario is Missing! staff

References

- ^ Vincent L. Turzo (August 4, 1993). SOFTWARE TOOLWORKS REPORTS 41-PERCENT GAIN IN REVENUES FOR THE JUNE QUARTER; QUARTERLY LOSS NARROWS TO -2 CENTS PER SHARE. Free Online Library. Retrieved July 1, 2024. (Archived January 18, 2018, 12:24:23 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ June 1993. Mario Is Missing!. GameFan 1(7). Page 18, 66. Retrieved July 1, 2024. (Archived via archive.today.)

- ^ July 1993. Mario Is Missing!. Nintendo Power (50). Page 26-27. Retrieved July 1, 2024. (Archived via archive.today.)

- ^ October 1993. Mario is Missing review (NES). Total!.

- ^ Pariona, Amber (November 3, 2017). "Which Are the 10 Largest Asian Countries By Area?". WorldAtlas.

- ^ Wang, Yi (July 20, 2016). "Dadu in the Yuan Dynasty" - A Century of Change: Beijing's Urban Structure in the 20th Century, illustrated ed.. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3319396330. Page 14. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Fang, Jun (May 23, 2014). China's Second Capital – Nanjing under the Ming, 1368-1644. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135008444. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ 北京三千年,定都八百载

- ^ http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/beijing/30785.htm

- ^ a b November 26, 2010. "People's Daily Online" - "The History of Tiananmen Gate". eBeijing. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ "Tian'anmen -- the Gate of Heavenly Peace". China.org.cn, China Internet Information Center. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ 2010. "Designer of Tiananmen". Beijing Attractions. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Miles, Kathy A. (2004). "Viewing Earth: How Much Can Be Seen from Space?". Starryskies.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018. (Archived February 12, 2006, 05:21:43 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Sweeney, Chris (August 11, 2010). "The World's 18 Strangest Gardens". Popular Mechanics.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (January 31, 1986). "Is the Great Wall of China the Only Manmade Object You Can See from Space?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (July 20, 2014). "Can You See the Great Wall of China from the Moon?". Snopes.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ "Seven Wonders of the Medieval World". Unmuseum.org.

- ^ Oberheu, Caroline (September 6, 2017). "The 7 Wonders of the Medieval World". WorldAtlas.

- ^ Slavicek, Louise Chipley (2009). "The Human Cost of Building the First Great Wall" - The Great Wall of China. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438121413. Page 33–35. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ Evans, Thammy (2006). "Myths" - Great Wall of China: Beijing & Northern China, illustrated ed.. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1841621586. Page 11. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ "Labor Force of Great Wall". Travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Qin Dynasty Great Wall". travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests". en.tiantanpark.com. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ April 26, 2016. "Big Ben 'bongs' to be silenced for £29m refurbishment". BBC News. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Allen Brown, Reginald; Curnow, P (1984). Tower of London, Greater London: Department of the Environment Official Handbook, Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-671148-9.

- ^ Wikipedia contributors (January 4, 2018). "List of largest domes". Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Wilton, Katherine (January 6, 2015). "The Cross on Mount Royal: a Storied History". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ "The Stadium". Parc Olympique. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ January 6, 2015. "The Cross on Mount Royal: a Storied History". Parc olympique (English). Retrieved June 21, 2024. (Archived April 14, 2024, 03:37:06 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ a b "Церковь Покрова Пресвятой Богоматери". Панорама 360 (Russian). Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ Berton, Kathleen (1977). "St. Basil's" - Moscow: An Architectural History. St. Martin's Press. Page 40–43. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Shvidkovsky, Dmitry; Wood, Antony (translator) (2007). "St Basil's Cathedral and the Architectural Tastes of Ivan the Terrible" - Russian Architecture and the West illustrated ed.. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300109122. Page 126.

- ^ a b Michelman, Fran (2007). "Alexander Gorsky". Abt.org.

- ^ July 11, 2017. "Bolshoi Theatre Postpones Rudolf Nureyev Ballet". BBC News, BBC. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna (May 4, 1985). "HOW REALISM IN MIME AND ROMANTIC BALLET BEGAN". The New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ 2015. "History". Bolshoi.ru. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- ^ "Tsar Bell". Kreml.ru. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Timofeychev, Alexey (October 24, 2017). "The Tsar Bell: How Russian Craftsmen Made the Impossible". Russia Beyond. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Richardson, Dan; Reynolds, Jonathon (February 2, 2009). "Red Square and the Kremlin" - The Rough Guide to Moscow. ISBN 978-1848361782. Page 85. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ August 15, 2017. "Asian elephant" - Smithsonian's National Zoo. The Smithsonian. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ Morell, Virginia (1996). "Surrounded! - Civilization Is Encroaching on Nairobi National Park in Kenya - Nairobi's Wild Side" - International Wildlife, vol. 26, no. 4. Findarticles.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018. (Archived January 15, 2005, 23:03:46 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ 2016. "Maasai Peoples - Enkuraru Headdress" - Spencer Museum of Art. University of Kansas. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ 2012. "Maasai Warrior with Red Ochre Face Paint, Kenya". Carol Beckwith & Angela Fisher. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ "African Tribe List". interesting-africa-facts.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ "People of Africa". africanholocaust.net. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ Temps, Dietmar. "Morani - The Warriorhood Tradition of the Kenyan Tribes". dietmartemps.com. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ "Nairobi National Museum". National Museums of Kenya. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Leakey, R. E. F. (April 13, 1973). "Evidence for an Advanced Plio-Pleistocene Hominid from East Rudolf, Kenya." - Nature, vol. 242, no. 5398, doi:10.1038/242447a0. Page 447–450. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History (March 1, 2010). "Homo rudolfensis". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program, The Smithsonian.

- ^ The Largest Countries in Europe. World Atlas. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Rupp, Rebecca (January 8, 2015). Are French Fries Truly French?. National Geographic. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Dietz, Frieda Meredith (1948). "Latin Manhattan" - Let's Talk Turkey: Adventures and Recipes of the White Turkey Inn. Dietz Press. Page 79. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Lloyd, Harvey (1999). "The Appeal of Buenos Aires" - Voyages: The Romance of Cruising. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-4617-0. Page 115. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Ruhl, Marcus (2013). "Ancient Roman Colosseum in Rome". Ancient Roman Colosseum: History, Architecture, Purpose. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Sistine (Adj.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Bambach, Carmen C. (November 5, 2017). "A New Artistic Vision" - Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1588396372. Page 83. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ April 22, 1989. "Michelangelo Didn't Lie Down on the Job". The New York Times. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Coins into the Trevi Fountain". WelcomeToRome.net. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Richards, Rand (2007). "The Gold Rush (1848-1849)" - Historic San Francisco: A Concise History and Guide, illustrated ed.. Heritage House Publishers. ISBN 978-1879367050. Page 57–62. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Fog Horns". Golden Gate Bridge Highway & Transportation District (goldengatebridge.org). Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Bridge Design and Construction Statistics". Golden Gate Bridge Highway & Transportation District (Goldengatebridge.org). Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard (June 27, 2017). "Two Bay Area Bridges - The Golden Gate and San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge". U.S. Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration (fhwa.dot.gov). Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Serrell, Allison (January 17, 2018). "What Causes the Fog in San Francisco?". TripSavvy. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Coit Tower". The Official San Francisco Recreation and Park Department Website. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ United States, Department of the Interior, San Francisco (2008). "Background" - National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet [Coit Tower]. NPGallery. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ 2018. "Pyramid Facts". Pyramidcenter.com, Transamerica Corporation. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ November 1993. Nintendo Magazine System (AU) Issue #8. Page 28-29.

- ^ June 1993. Electronic Gaming Monthly #47. Page 28.

- ^ July 19, 2014. "Software Toolworks reports 41-percent gain in revenues for the June quarter; quarterly loss narrows to -2 cents per share.". PR Newswire Association LLC.

- ^ Henrik Markarian (former Director of Software Development at The Software Toolworks) profile. LinkedIn. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

| Super Mario games | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Platformers | Super Mario series | Main | Super Mario Bros. (1985, NES) • Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels (1986, FDS) • Super Mario Bros. 2 (1988, NES) • Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988, NES) • Super Mario Land (1989, GB) • Super Mario World (1990, SNES) • Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins (1992, GB) • Super Mario 64 (1996, N64) • Super Mario Sunshine (2002, GCN) • New Super Mario Bros. (2006, DS) • Super Mario Galaxy (2007, Wii) • New Super Mario Bros. Wii (2009, Wii) • Super Mario Galaxy 2 (2010, Wii) • Super Mario 3D Land (2011, 3DS) • New Super Mario Bros. 2 (2012, 3DS) • New Super Mario Bros. U (2012, Wii U) • Super Mario 3D World (2013, Wii U) • Super Mario Maker (2015, Wii U) • Super Mario Run (2016, iOS/iPadOS/Android) • Super Mario Odyssey (2017, Switch) • Super Mario Maker 2 (2019, Switch) • Super Mario Bros. Wonder (2023, Switch) |

| Reissues | VS. Super Mario Bros. (1986, VS) • Super Mario Bros. (1986, G&W) • All Night Nippon: Super Mario Bros. (1986, FDS) • Super Mario Bros. (1989, NGW) • Super Mario Bros. 3 (1990, NGW) • Super Mario World (1991, NGW) • Super Mario All-Stars (1993, SNES) • Super Mario All-Stars + Super Mario World (1994, SNES) • BS Super Mario USA (1996, SNES) • BS Super Mario Collection (1997, SNES) • Super Mario Bros. Deluxe (1999, GBC) • Super Mario Advance (2001, GBA) • Super Mario World: Super Mario Advance 2 (2001, GBA) • Super Mario Advance 4: Super Mario Bros. 3 (2003, GBA) • Classic NES Series (2004–2005, GBA) • Super Mario 64 DS (2004, DS) • Super Mario All-Stars Limited Edition (2010, Wii) • Super Mario Maker for Nintendo 3DS (2016, 3DS) • New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe (2019, Switch) • Super Mario 3D All-Stars (2020, Switch) • Game & Watch: Super Mario Bros. (2020, G&W) • Super Mario 3D World + Bowser's Fury (2021, Switch) | ||

| Related games | Super Mario Bros. Special (1986, computer) • Wario Land: Super Mario Land 3 (1994, GB) • Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island (1995, SNES) • New Super Luigi U (2013, Wii U) • Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker (2014, Wii U) • Super Mario Bros. 35 (2020, Switch) • Bowser's Fury (2021, Switch) | ||

| Canceled games | Super Mario's Wacky Worlds (CD-i) • Mario Takes America (CD-i) • VB Mario Land (VB) • Super Mario 64 2 (N64DD) | ||

| Donkey Kong series | Donkey Kong (1981, arcade) • Donkey Kong (1994, GB) | ||

| Mario vs. Donkey Kong series | Mario vs. Donkey Kong (2004, GBA) • Mario vs. Donkey Kong 2: March of the Minis (2006, DS) • Mario vs. Donkey Kong: Minis March Again! (2009, DSiWare) • Mario vs. Donkey Kong: Mini-Land Mayhem! (2010, DS) • Mario and Donkey Kong: Minis on the Move (2013, 3DS) • Mario vs. Donkey Kong: Tipping Stars (2015, 3DS/Wii U) • Mini Mario & Friends: amiibo Challenge (2016, 3DS/Wii U) | ||

| Mario Bros. series | Mario Bros. (1983, arcade) • Mario Bros. Special (1984, computer) • Punch Ball Mario Bros. (1984, computer) • Mario Clash (1995, VB) | ||

| Wrecking Crew series | VS. Wrecking Crew (1984, VS) • Wrecking Crew (1985, NES) • Wrecking Crew '98 (1998, SFC) | ||

| Other | Mario Bros. (1983, G&W) • Mario's Cement Factory (1983, G&W) • Mario & Wario (1993, SNES) • Hotel Mario (1994, CD-i) • Super Princess Peach (2005, DS) • Princess Peach: Showtime! (2024, Switch) | ||

| Reissues | Crazy Kong (1981, arcade) • Donkey Kong (1982, G&W) • Donkey Kong (1982, tabletop) • Mario Bros. Returns (1988, FDS) • Donkey Kong (1994, NGW) • Yoshi's Island: Super Mario Advance 3 (2002, GBA) • Donkey Kong/Donkey Kong Junior/Mario Bros. (2004, arcade) • Virtual Console (2006–2016, Wii/3DS/Wii U) • Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker (2018, Switch/3DS) • Mario vs. Donkey Kong (2024, Switch) | ||

| Tech demos | Super Mario 128 (2000, GCN) • New Super Mario Bros. Mii (2011, Wii U) | ||

| Mario Kart series | Main | Super Mario Kart (1992, SNES) • Mario Kart 64 (1996, N64) • Mario Kart: Super Circuit (2001, GBA) • Mario Kart: Double Dash!! (2003, GCN) • Mario Kart DS (2005, DS) • Mario Kart Wii (2008, Wii) • Mario Kart 7 (2011, 3DS) • Mario Kart 8 (2014, Wii U) • Mario Kart Tour (2019, iOS/iPadOS/Android) • Mario Kart (Switch 2) | |

| Arcade | Mario Kart Arcade GP (2005, arcade) • Mario Kart Arcade GP 2 (2007, arcade) • Mario Kart Arcade GP DX (2013, arcade) • Mario Kart Arcade GP VR (2017, arcade) | ||

| Other | Mario Kart Live: Home Circuit (2020, Switch) | ||

| Ports | Mario Kart 8 Deluxe (2017, Switch) | ||

| Mario Party series | Main | Mario Party (1998, N64) • Mario Party 2 (1999, N64) • Mario Party 3 (2000, N64) • Mario Party 4 (2002, GCN) • Mario Party 5 (2003, GCN) • Mario Party 6 (2004, GCN) • Mario Party 7 (2005, GCN) • Mario Party 8 (2007, Wii) • Mario Party 9 (2012, Wii) • Mario Party 10 (2015, Wii U) • Super Mario Party (2018, Switch) • Mario Party Superstars (2021, Switch) • Super Mario Party Jamboree (2024, Switch) | |

| Handheld | Mario Party Advance (2005, GBA) • Mario Party DS (2007, DS) • Mario Party: Island Tour (2013, 3DS) • Mario Party: Star Rush (2016, 3DS) • Mario Party: The Top 100 (2017, 3DS) | ||

| Arcade | Super Mario Fushigi no Korokoro Party (2004, arcade) • Super Mario Fushigi no Korokoro Party 2 (2005, arcade) • Mario Party Fushigi no Korokoro Catcher (2009, arcade) • Mario Party Kurukuru Carnival (2012, arcade) • Mario Party Fushigi no Korokoro Catcher 2 (2013, arcade) • Mario Party Challenge World (2016, arcade) | ||

| Other | Mario Party 4 (2002, Adobe Flash) • Mario Party-e (2003, GBA) | ||

| Sports games | Mario Golf series | Golf (1984, NES) • Stroke & Match Golf (1984, VS. System) • Golf: Japan Course (1987, FDS) • Golf: U.S. Course (1987, FDS) • Golf (1989, GB) • NES Open Tournament Golf (1991, NES) • Mario Golf (1999, N64) • Mario Golf (1999, GBC) • Mobile Golf (2001, GBC) • Mario Golf: Toadstool Tour (2003, GCN) • Mario Golf: Advance Tour (2004, GBA) • Mario Golf: World Tour (2014, 3DS) • Mario Golf: Super Rush (2021, Switch) | |

| Mario Tennis series | Mario's Tennis (1995, VB) • Mario Tennis (2000, N64) • Mario Tennis (2000, GBC) • Mario Power Tennis (2004, GCN) • Mario Tennis: Power Tour (2005, GBA) (Bicep Pump [Unknown, Adobe Flash] • Reflex Rally [Unknown, Adobe Flash]) • Mario Tennis Open (2012, 3DS) • Mario Tennis: Ultra Smash (2015, Wii U) • Mario Tennis Aces (2018, Switch) | ||

| Super Mario Stadium series | Mario Superstar Baseball (2005, GCN) • Mario Super Sluggers (2008, Wii) | ||

| Mario Strikers series | Super Mario Strikers (2005, GCN) • Mario Strikers Charged (2007, Wii) • Mario Strikers: Battle League (2022, Switch) | ||

| Famicom Grand Prix series | Famicom Grand Prix: F1 Race (1987, FDS) • Famicom Grand Prix II: 3D Hot Rally (1988, FDS) | ||

| Other | Donkey Kong Hockey (1984, G&W) • Baseball (1989, GB) • Super Mario Race (1992, GwB) • Easy Racer (1996, SNES) • Mario Hoops 3-on-3 (2006, DS) • Mario Sports Mix (2010, Wii) • Mario Sports Superstars (2017, 3DS) • LEGO Super Mario Goal (2024, Sky Italia) | ||

| Canceled games | Super Mario Spikers (Wii) | ||

| Role-playing games | Paper Mario series | Paper Mario (2000, N64) • Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (2004, GCN) • Super Paper Mario (2007, Wii) • Paper Mario: Sticker Star (2012, 3DS) • Paper Mario: Color Splash (2016, Wii U) • Paper Mario: The Origami King (2020, Switch) | |

| Mario & Luigi series | Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga (2003, GBA) • Mario & Luigi: Partners in Time (2005, DS) • Mario & Luigi: Bowser's Inside Story (2009, DS) • Mario & Luigi: Dream Team (2013, 3DS) • Mario & Luigi: Paper Jam (2015, 3DS) • Mario & Luigi: Brothership (2024, Switch) | ||

| Other | Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars (1996, SNES) | ||

| Remakes | Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga + Bowser's Minions (2017, 3DS) • Mario & Luigi: Bowser's Inside Story + Bowser Jr.'s Journey (2018, 3DS) • Super Mario RPG (2023, Switch) • Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door (2024, Switch) | ||

| Dr. Mario series | Main | Dr. Mario (1990, NES/GB) • Dr. Mario 64 (2001, N64) • Dr. Mario Online Rx (2008, WiiWare) • Dr. Mario Express (2008, DSiWare) • Dr. Luigi (2013, Wii U) • Dr. Mario: Miracle Cure (2015, 3DS) • Dr. Mario World (2019, iOS/iPadOS/Android) | |

| Other | Dr. Mario (1993, GwB) | ||

| Remakes | Tetris & Dr. Mario (1994, SNES) • Nintendo Puzzle Collection (2003, GCN) • Dr. Mario & Puzzle League (2005, GBA) | ||

| Luigi's Mansion series | Main | Luigi's Mansion (2001, GCN) • Luigi's Mansion: Dark Moon (2013, 3DS) • Luigi's Mansion 3 (2019, Switch) | |

| Arcade | Luigi's Mansion Arcade (2015, arcade) | ||

| Remakes | Luigi's Mansion (2018, 3DS) • Luigi's Mansion 2 HD (2024, Switch) | ||

| Educational games | Mario Discovery Series | Mario is Missing! (1992, MS-DOS) • Mario is Missing! (1993, SNES) • Mario is Missing! (1993, NES) • Mario's Time Machine (1993, MS-DOS) • Mario's Time Machine (1993, SNES) • Mario's Time Machine (1994, NES) • Mario's Early Years! Fun with Letters (1993, MS-DOS/SNES) • Mario's Early Years! Fun with Numbers (1994, MS-DOS/SNES) • Mario's Early Years! Preschool Fun (1994, MS-DOS/SNES) | |

| Mario Teaches Typing series | Mario Teaches Typing (1991, MS-DOS) • Mario Teaches Typing 2 (1996, MS-DOS) | ||

| Other | Family BASIC (1984, FC) • Super Mario Bros. & Friends: When I Grow Up (1991, MS-DOS) | ||

| Ports | Mario's Early Years! CD-ROM Collection (1995, MS-DOS) | ||

| Art utilities | Mario Artist series | Mario Artist: Paint Studio (1999, N64DD) • Mario Artist: Talent Studio (2000, N64DD) • Mario Artist: Communication Kit (2000, N64DD) • Mario Artist: Polygon Studio (2000, N64DD) | |

| Other | I am a teacher: Super Mario Sweater (1986, FDS) • Super Mario Bros. Print World (1991, MS-DOS) • Mario Paint (1992, SNES) • Super Mario Collection Screen Saver (1997, PC) • Mario no Photopi (1998, N64) • Mario Family (2001, GBC) | ||

| Miscellaneous | Picross series | Mario's Picross (1995, GB) • Mario's Super Picross (1995, SFC) • Picross 2 (1996, GB) • Picross NP Vol. 6 (2000, SFC) | |

| LCD handhelds | Mario's Bombs Away (1983, G&W) • Mario's Egg Catch (1990, SMBW) • Luigi's Hammer Toss (1990, SMBW) • Princess Toadstool's Castle Run (1990, SMBW) • Mario the Juggler (1991, G&W) | ||

| Pinball | Pinball (1984, NES) • Super Mario Bros. (1992, arcade) • Super Mario Bros. Mushroom World (1992, arcade) • Mario Pinball Land (2004, GBA) | ||

| Arcade | Mario Roulette (1991, arcade) • Piccadilly Circus: Super Mario Bros. 3 (1991, arcade) • Mario World (1991, arcade) • Terebi Denwa: Super Mario World (1992, arcade) • Super Mario World Popcorn (1992, arcade) • Pika Pika Mario (1992, arcade) • Janken Fukubiki: Super Mario World (1992, arcade) • Koopa Taiji (1993, arcade) • Būbū Mario (1993, arcade) • Mario Undōkai (1993, arcade) • Super Mario World (1993, arcade) • Super Mario Kart: Doki Doki Race (1994, arcade) • Mario Bowl (1995, arcade) • Super Mario Attack (1996, arcade) • Super Donkey Kong 2 Swanky no Bonus Slot (1996, arcade) • Donkey Kong (1996, arcade) • Mario Kart 64 (1996, arcade) • Super Mario 64 (1997, arcade) • Super Mario Bros. 3 (Unknown, arcade) • Super Mario World (Unknown, arcade) • Guru Guru Mario (Unknown, arcade) • Dokidoki Mario Chance! (2003, arcade) • Super Mario Fushigi no Janjan Land (2003, arcade) • New Super Mario Bros. Wii Coin World (2011, arcade) | ||

| Browser | Mario Net Quest (1997, Adobe Shockwave) • Mario's Memory Madness (1998, Adobe Shockwave) • Crazy Counting (1999, Adobe Shockwave) • Dinky Rinky (1999, Adobe Shockwave) • Goodness Rakes (1999, Adobe Shockwave) • Melon Mayhem (1999, Adobe Shockwave) • Nomiss (1999, Adobe Shockwave) • Wario's Whack Attack (1998, Adobe Shockwave) • The Lab (The Bookshelf • The Drafting Table • PolterCue • Ask Madame Clairvoya) (2001, Adobe Flash) • Mario Trivia (Unknown, Adobe Flash) • Mario Memory (Unknown, Adobe Flash) • Virus Attack! (Unknown, Adobe Flash) • Mini-Mario Factory Game! (2004, Adobe Flash) • Bill Bounce (2004, Adobe Flash) • Mario Party 7 Bon Voyage Quiz (2005, Adobe Flash) • Super Mario Strikers (2005, Adobe Flash) • Dr. Mario Vitamin Toss (2005, Adobe Flash) • Bowser's Lair Hockey (2005, Adobe Flash) • Heads-Up (2005, Adobe Flash) • Parasol Fall (2005, Adobe Flash) • Dribble Skillz (2006, Adobe Flash) • Superstar Shootout (2006, Adobe Flash) • Cannon Kaos (2006, Adobe Flash) • 1-Up Hunt! (2006, Adobe Flash) • Super Paper Mario Memory Match (2007, Adobe Flash) • Are You Smarter Than Mario? (2008, Adobe Flash) • Play Nintendo activities (2014–present) | ||

| DSiWare applications | Mario Calculator (2009, DSiWare) • Mario Clock (2009, DSiWare) • Nintendo DSi Metronome (2010, DSiWare) | ||

| Other games | Alleyway (1989, GB) • Yoshi's Safari (1993, SNES) • UNDAKE30 Same Game (1995, SFC) • Mario's Game Gallery (1995, MS-DOS) • Mario's FUNdamentals (1998, Windows) • Yakuman DS (2005, DS) | ||

| Tech demos | NDDEMO (2001, GCN) • Mario's Face (Unknown, DS) | ||

| Crossovers | Game & Watch Gallery series | Game & Watch Gallery (1997, GB) • Game & Watch Gallery 2 (1997, GB) • Game & Watch Gallery 3 (1999, GBC) • Game & Watch Gallery 4 (2002, GBA) | |

| Super Smash Bros. series | Super Smash Bros. (1999, N64) • Super Smash Bros. Melee (2001, GCN) • Super Smash Bros. Brawl (2008, Wii) • Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS (2014, 3DS) • Super Smash Bros. for Wii U (2014, Wii U) • Super Smash Bros. Ultimate (2018, Switch) | ||

| Itadaki Street series | Itadaki Street DS (2007, DS) • Fortune Street (2011, Wii) | ||

| Mario & Sonic series | Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games (2007, Wii) • Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games (2008, DS) • Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Winter Games (2009, Wii) • Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Winter Games (2009, DS) • Mario & Sonic at the London 2012 Olympic Games (2011, Wii) • Mario & Sonic at the London 2012 Olympic Games (2012, 3DS) • Mario & Sonic at the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games (2013, Wii U) • Mario & Sonic at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games (2016, Wii U) • Mario & Sonic at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games (2016, 3DS) • Mario & Sonic at the Rio 2016 Olympic Games Arcade Edition (2016, arcade) • Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 (2019, Switch) • Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 - Arcade Edition (2020, arcade) | ||

| NES Remix series | Main | NES Remix (2013, Wii U) • NES Remix 2 (2014, Wii U) | |

| Reissues | NES Remix Pack (2014, Wii U) • Ultimate NES Remix (2014, 3DS) | ||

| Mario + Rabbids series | Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle (2017, Switch) • Mario + Rabbids Sparks of Hope (2022, Switch) | ||

| Other | Excitebike: Bun Bun Mario Battle (1997, SNES) • NBA Street V3 (2005, GCN) • Dance Dance Revolution: Mario Mix (2005, GCN) • SSX on Tour (2005, GCN) • Tetris DS (2006, DS) • Captain Rainbow (2008, Wii) • Art Style: PiCTOBiTS (2009, DSiWare) • Nintendo Land (2012, Wii U) • Puzzle & Dragons: Super Mario Bros. Edition (2015, 3DS) • Nintendo World Championships: NES Edition (2024, Switch) | ||

| Family Computer / Nintendo Entertainment System games | ||

|---|---|---|

| Super Mario franchise | Donkey Kong (1983) • Mario Bros. (1983) • Pinball (1984) • Golf (1984) • Family BASIC† (1984) • Family BASIC V3† (1985) • Wrecking Crew (1985) • Super Mario Bros. (1985) • Super Mario Bros. 2 (1988) • Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988) • Dr. Mario (1990) • NES Open Tournament Golf (1991) • Mario is Missing!* (1993) • Mario's Time Machine* (1994) | |

| Donkey Kong franchise | Donkey Kong (1983) • Donkey Kong Jr. (1983) • Donkey Kong Jr. + Jr. Sansū Lesson† (1983) • Donkey Kong Jr. Math (1983) • Donkey Kong 3 (1984) • Donkey Kong Classics* (1988) | |

| Yoshi franchise | Yoshi (1991) • Yoshi's Cookie (1992) | |

| Wario franchise | Wario's Woods (1994) | |

| Family Computer Disk System | Golf (1986) • Super Mario Bros. (1986) • Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels‡ (1986) • I am a teacher: Super Mario Sweater‡ (1986) • All Night Nippon: Super Mario Bros.‡ (1986) • Golf: Japan Course‡ (1987) • Golf: U.S. Course‡ (1987) • Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic‡ (1987) • Famicom Grand Prix: F1 Race‡ (1987) • Donkey Kong^ (1988) • Famicom Grand Prix II: 3D Hot Rally‡ (1988) • Donkey Kong Jr.^ (1988) • Mario Bros. Returns^ (1988) • Wrecking Crew^ (1989) • Pinball^ (1989) | |

| Miscellaneous | Nintendo World Championships 1990* (1990) • Nintendo Campus Challenge* (1991) | |