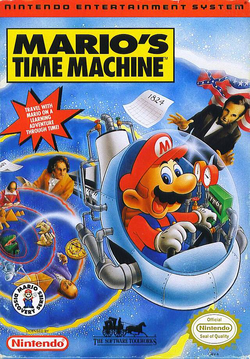

Mario's Time Machine (Nintendo Entertainment System)

| Mario's Time Machine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

For alternate box art, see the game's gallery. | |||

| Developer | The Software Toolworks Radical Entertainment | ||

| Publisher | The Software Toolworks | ||

| Platform(s) | Nintendo Entertainment System | ||

| Release date | June 1994[1] | ||

| Language(s) | English (United States) | ||

| Genre | Educational | ||

| Rating(s) |

| ||

| Mode(s) | Single-player | ||

| Format | NES:

| ||

| Input | NES:

| ||

| Serial code(s) | NES-TM | ||

Mario's Time Machine, stylised as Mario's Time Machine! on the title screen, is an educational game developed by Radical Entertainment that was released for the NES in June 1994.[1] It is the successor to Mario is Missing! It is intended to teach younger players basic world history and was the last game in the Mario Discovery series. This game is mostly based on Super Mario World, which was a common theme of the Mario Discovery series and Super Mario educational games.

Story[edit]

In the year 1993, Bowser uses a time machine called a "Timulator," traveling backwards to different points in human history and stealing significant artifacts to place in his personal museum inside his castle. With his collection nearly completed, Bowser gloats that not even Mario can stop him now. Mario realizes that history will change forever if he does nothing, so it is up to Mario to use Bowser's own device against him by returning the artifacts to their proper places in time.

Bowser plans to destroy his time machine, deliberately planning to irreversibly damage history and send the world back to the Dark Ages.[2] His Museum has been fully built and already established itself with history's greatest artifacts. Yoshi joins Mario in his quest to stop Bowser's plot, but instead gets captured when he scouts ahead. In addition to fixing the timeline, Mario must also rescue Yoshi from peril.

Gameplay[edit]

Unlike Mario is Missing!, the NES release is virtually a different game with little resemblance to its previous incarnations, traveling to very different time periods and restoring entirely different objects. Bowser's Museum is largely a hall with seven doors ending with Bowser's chamber. Behind each door is a Mario Bros.-style mini-game involving Koopas with a unique item that can be acquired if Mario defeats all of them. The Timulator is in the bottom center of each room, and it is a Warp Pipe with a transparent box. Inside the Timulator, Mario can select pre-determined time periods rather than input them manually, although the location is not disclosed. Once warped across time and space, Mario will arrive at a short platforming land with enemies (Koopas, Bodyslam Koopas, and Walking Turnips) and occasionally indigenous inhabitants of the time period. There are also information boxes which describe the location. Mario must take the item acquired in the mini-game and return it to the appropriate spot - if it is in the incorrect place then it will return to the clutches of the Koopas via a bird (or flying saucer when on the moon), but if Mario is right then he will complete that area. There are two artifacts in each door, so Mario must enter a door at least twice before he can close that section of the museum. After all the doors of the museum are cleared, the deeper part of the castle is available after Mario passes a random History Test about what he has learned. After beating Bowser, a key will be released and Mario will free Yoshi from his cage. In the end, Mario and Yoshi pose next to a saddened, crying Bowser.

Time periods[edit]

Here is a chart of the location and artifact in chronological order.

- 80M BC — Cretaceous Period (Dinosaur Egg)

- 776 BC — Olympia (Torch)

- 31 BC — Egypt (Cleopatra's Throne)

- 1192 — Japan (Minamoto no Yoritomo's Sword)

- 1520 — The Trinidad (Ferdinand Magellan's Steering Wheel)

- 1602 — United Kingdom (William Shakespeare's Quill Pen)

- 1687 — Cambridge University (Isaac Newton's Apple)

- 1862 — Gettysburg (Abraham Lincoln's Stovepipe Hat)

- 1879 — Menlo Park (Thomas Edison's Light Bulb)

- 1903 — Kitty Hawk (the Wright brothers' Propeller)

- 1905 — Germany (Albert Einstein's Physics Equation)

- 1947 — India (Indian Flag)

- 1969 — Moon (American Flag)

- 1989 — Berlin Wall (Sledgehammer)

Historical inaccuracies and other errors[edit]

Despite Mario's Time Machine being intended as an educational game, the various versions contain many errors in regards to its historical facts. The NES version has:

- Germany (1905)

- Albert Einstein says that he moved to the United States in the 1930s when Mario meets him in 1905. Additionally, Einstein appears to be middle-aged, despite only being 26 years old at the time.

Reception[edit]

Since its release, Mario's Time Machine has received negative reception. It holds an aggregate score of 60.25% on Game Rankings based on two reviews. Nintendo Power gave it a 10.6 out of 20, while Electronic Gaming Monthly gave it a slightly better rating of 6.75 out of 10. GameSpy's Brian Altano and Brian Miggels criticized the ending of this version for its depiction of Bowser crying.[3] The Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Good Game described it as one of many "awful" games that used the Super Mario license, and said that it was "too complicated" for its young target audience.[4] Similarly, authors David Wesley and Gloria Barczak include both it and Mario is Missing! in the "flood" of poor-quality 1990s Super Mario games and media made by third parties with no supervision from Nintendo, accusing these two games, Mario's FUNdamentals, and the Super Mario Bros. film of "nearly destroy[ing]" the entire franchise.[5] Patrick Felicia, who focuses on learning through video games, criticizes Mario's Time Machine and Mario is Missing! for their "mismatch" between the gameplay and the presentation, while also praising Super Mario Bros. due to everything being in service of platforming.[6]

Development[edit]

According to programmer Carlos Justiniano, Mario's Time Machine was behind schedule when he began working on it, and the team developed it over the course of several weeks.[7] Lead artist Maude Church, who worked primarily on adding animations to Mario's Time Machine Deluxe, also said that Nintendo did not interfere with the game's development; they were mostly concerned with how Mario looked.[8] The team was also focused on being historically accurate - though for the final level that featured the game's developers within the game itself, it was simply a "little personal moment with a laugh".[8]

References to other games[edit]

- Donkey Kong Jr.: The titular character makes a cameo as a painting.

- Mario Bros.: The method of collecting objects involves defeating three Koopas in a style similar to this game. Unlike in the original game, the pipes are able to be entered by Mario, and can be used to exit to the main part of the museum.

- Super Mario Bros. 3: Bowser's sprite appears to be a modified version of his sprite from this game. The Koopalings have a cameo as statues and torches throughout the castle.

- Super Mario World: Most of the other sprites, including those for Mario, Yoshi, and the Koopas, are those from this game, though modified to fit the graphical limitations of the NES. A number of other assets directly reference this game, such as the opening where Mario and Yoshi walk up to Bowser's Museum, which is identical to the cutscene shown before Mario enters a Ghost House or Castle, except Yoshi runs inside the museum after Mario dismounts him rather than waiting outside. Finally, the Dinosaur Egg also bears some slight resemblance to a Yoshi's egg.

- Mario is Missing!: The music used for Rome and Montreal is reused in Cambridge University in both games, and the music used during the ending is also the title music.

References in later games[edit]

- Nintendo World Championships: NES Edition: Mario's Time Machine can be selected as the player's favorite NES game on their profile.

Gallery[edit]

- Main article: Gallery:Mario's Time Machine

Media[edit]

Staff[edit]

- Main article: List of Mario's Time Machine staff

References[edit]

- ^ a b Nintendo. Complete List of Games (PDF). Retrieved March 21, 2016. (Archived May 1, 2005, 15:00:12 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Mario's Time Machine NES instruction booklet, page 1.

- ^ Altano, Brian; Miggels, Brian (August 14, 2009). "The Worst NES Endings, and Why We Deserved Better". GameSpy. Retrieved December 20, 2017. (Archived August 15, 2009, 22:45:12 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ May 11, 2009. "Edutainment" - Good Game. ABC. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Wesley, David T. A.; Barczak, Gloria (June 28, 2010). "Nintendo's Dark Ages" - Innovation and Marketing in the Video Game Industry: Avoiding the Performance Trap. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0566091674. Page 40.

- ^ Felicia, Patrick (January 31, 2011). "Matching Basic (Cognitive) Activities" - Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Information Science Reference. ISBN 978-1609604950. Page 334.

- ^ Carlos Justiniano's personal website. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Time Turner (2017). Interview with Maude Church. Super Mario Boards. Retrieved October 7, 2017.