Mario's Time Machine (Super Nintendo Entertainment System): Difference between revisions

Bowserbros (talk | contribs) |

Apikachu68 (talk | contribs) m (→Historical inaccuracies and other errors: Removed contraction.) |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

;[[Calcutta]] (1947) | ;[[Calcutta]] (1947) | ||

*If Mario shows the [[Flag (India)|Indian flag]] to the British judge, he angrily states that he | *If Mario shows the [[Flag (India)|Indian flag]] to the British judge, he angrily states that he would rather see the {{wp|Saint George's Cross}}, referring to the {{wp|flag of England}}. However, variations of the English flag were only used by the {{wp|British Raj}} for coronation standards and naval ensigns; within the Raj, the regular Union Jack was considered the "national flag," while international representation of the Raj used the {{wp|Governor-General of India}}'s standard and the {{wp|Red Ensign#India|civil ensign}} (both of which incorporated the Union Jack). | ||

;[[Cambridge]] (1687) | ;[[Cambridge]] (1687) | ||

Revision as of 18:25, December 14, 2024

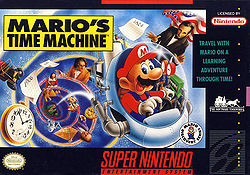

| Mario's Time Machine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

For alternate box art, see the game's gallery. | |||

| Developer | The Software Toolworks | ||

| Publisher | The Software Toolworks | ||

| Platform(s) | SNES | ||

| Release date | |||

| Language(s) | English (United States) German | ||

| Genre | Educational | ||

| Rating(s) |

| ||

| Mode(s) | Single player | ||

| Format | Super NES: | ||

| Input | Super NES:

| ||

| Serial code(s) | |||

Mario's Time Machine is a port of the DOS game of the same name released in December 1993.

Story

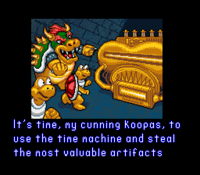

In the year 1993, Bowser uses a time machine called a "Timulator," traveling backwards to different points in human history and stealing significant artifacts to place in his personal museum inside his castle. With his collection nearly completed, Bowser gloats that not even Mario can stop him now. Mario realizes that history will change forever if he does nothing, so it is up to Mario to use Bowser's own device against him by returning the artifacts to their proper places in time.

Bowser plans to destroy his time machine, deliberately planning to irreversibly damage history and send the world back to the Dark Ages.[2]

Gameplay

Being a port of the PC release, this version has a few changes to the original game. There is less content overall, so Mario travels to fewer time periods, and there are some graphical changes such as the design of the time machine. During the sequence on time's waves, Mario can move in all directions rather than just forward due to the use of Mode 7 on the water, and he must go in a whirlpool after collecting ten mushrooms. The true ending is similar to the DOS version, only Bowser's puddle remains on the ground throughout the entire credits, and in addition, Bowser only gapes upon noticing the T-Rex foot coming down on him.

Time periods

Here is a chart of the location and artifact in chronological order.

- 369 BC — Athens (Plato's Republic)

- 47 BC — Alexandria (Cleopatra's Staff)

- 1292 — Gobi Desert (Marco Polo's Print Block)

- 1429 — Orleans (Joan of Arc's Shield)

- 1455 — Mainz (Johann Gutenberg's Metal Type)

- 1503 — Florence (Michelangelo Buonarroti's Chisel)

- 1505 — Florence (Leonardo da Vinci's Notebook)

- 1521 — Pacific Ocean (Ferdinand Magellan's Astrolabe)

- 1595 — England (Queen Elizabeth I's Crown)

- 1601 — Stratford-upon-Avon (William Shakespeare's Skull)

- 1687 — Cambridge (Isaac Newton's Apple)

- 1776 — Philadelphia (Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence)

- 1824 — Vienna (Ludwig van Beethoven's Music)

- 1879 — Menlo Park (Thomas Edison's Filament)

- 1947 — Calcutta (Mahatma Gandhi's Flag)

Historical inaccuracies and other errors

Despite Mario's Time Machine being intended as an educational game, it contains many errors in regards to its historical facts.

- Alexandria (47 BC)

- This section centers on returning Cleopatra's staff to her so that she can reign over Egypt; however, she first reigned in 51 BC (despite one of Cleopatra's guards saying that she was "crowned" in 52 BC) at the bequest of her father and alongside her brother, Ptolemy XIII. She then took sole control after a civil war between her and her brother in 47 BC.[3]

- Cleopatra also says that her staff was passed down from her ancestors, although no such item exists in real life.

- Julius Caesar claims that he is allergic to cats; though his family line, in general, was afflicted with asthma,[4] Caesar is not known to have been allergic to or even afraid of cats.[5]

- Caesar also boasts about having conquered Pompeii, despite the town having been acquired by Roman general Sulla during the Social War in 89 BC,[6] before Caesar held any power.

- One of Cleopatra's guards asks Mario to give one of Cleopatra's handmaidens a Wooden Snake to demonstrate his love for her, and after receiving the gift, she makes a comment about being bitten by the "love scarab." Neither animal is associated with romance or love: snakes are the aggressive guardians of royalty,[7] and can also symbolize chaos, [8] while scarabs symbolize the arrival of the Sun and the reincarnation of humans.[9]

- Throughout several lines of dialogue, it is stated that "Ptolemy XI" is Cleopatra's father and "Ptolemy XII" is the brother that campaigns against Cleopatra. However, the numbers in their names are off by one: Ptolemy XII was the father and Ptolemy XIII was the brother.

- Several characters also use dates with before Christ; for example, when the handmaiden says that Caesar arrived in Egypt "in 48 B.C.". Though these dates are not incorrect, they would have not been used by people who lived close to fifty years before the birth of Jesus, and furthermore, this dating system was not created until 525.

- The history pages mention that Cleopatra had three sons with Mark Anthony, despite one of her children, Cleopatra Selene II, being female.

- Athens (369 BC)

- Aristotle is depicted as an old man in-game, but as Aristotle was born in 384 BC,[10] he would have only been fifteen years old. With that in mind, the rest of the interactions with him become anachronistic, as he only became Plato's student when he was seventeen or eighteen,[11] and thus, he has not yet formulated any of the theories that are discussed in-game.

- A councilman mentions that Plato's Academy was founded "in 387 B.C." - while technically correct, a dating system based on Jesus would not have been used by someone who lived over three hundred years before he was born.

- The same councilman also claims that the Academy will last for over nine hundred years. In reality, the Academy was destroyed in 86 BC.[12]

- He also does not know whether the god of wine's name is Dionysus or Bacchus, despite "Bacchus" being the name adopted by the Romans.

- The history page describes the Academy as the first "university," which is incorrect as it did not offer any degrees to its students.

- Calcutta (1947)

- If Mario shows the Indian flag to the British judge, he angrily states that he would rather see the Saint George's Cross, referring to the flag of England. However, variations of the English flag were only used by the British Raj for coronation standards and naval ensigns; within the Raj, the regular Union Jack was considered the "national flag," while international representation of the Raj used the Governor-General of India's standard and the civil ensign (both of which incorporated the Union Jack).

- Cambridge (1687)

- The discovery of calculus is attributed uniquely to Newton, despite Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz also discovering calculus around the same time as Newton, albeit independently; this led to a debate as to who should receive recognition for the discovery.[13]

- Several characters state that Newton's Principia has not yet been published, for example, when Edmund Halley says that he is still working on the rough draft, but the book was published on July 5,[14] even though the game takes place on December 25.

- Halley also says that he tracked a comet which orbited around the Earth in 1862. This is a typo; the comet passed by in 1682.[15]

- A lecturer says that, while Newton was in his twenties, he said that his mind was "remarkably fit for invention." This quote seems to have been sourced from Leon M. Lederman and Dick Teresi's The God Particle,[16] but the actual quote is "All this was in the two plague years of 1665 and 1666, for in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention and minded Mathematics and Philosophy more than at any time since."[17]

- If Mario offers Halley an apple, he replies that he has already eaten one today "so as to keep the doctor away." The proverb of "an apple a day keeps the doctor away," however, first appeared in the 1860s.[18]

- Florence (1503)

- Raphael Sanzio mentions that he is working on a portrait of the Pope, despite his portraits of Pope Julius II and Leo X being painted in 1511–12 and 1518-19, respectively.

- Raphael also says that Michelangelo Buonarroti's David is thirteen-and-a-half feet tall, but it is actually seventeen feet tall.

- An unnamed painter says that Michelangelo left the tutelage of Domenico Ghirlandaio simply because he was bored, but Ghirlandaio sent him to Lorenzo de' Medici as one of his best pupils.[19]

- The history pages erroneously state that Michelangelo himself "broke his contract" with Ghirlandaio solely because he wanted to study the statues in Medici's garden.

- The same painter also gives Mario some "Renaissance Purple" Paint in what is visibly a modern paint can. Additionally, the term "Renaissance" first appeared in 1858.[20]

- He also says that Michelangelo is interested in sculpting the Pope's tomb; although he approached the task enthusiastically, he was specifically commissioned by the Pope to construct the tomb.[21]

- Florence (1505)

- An old fresco painter describes Leonardo da Vinci as a "Renaissance Man.: The term "Renaissance" was not used during the period,[20] and the whole expression first appeared in 1906.[22]

- The history pages say that Europe was in a 1000-year "slumber" before the Renaissance, which brought a new age of science and art. However, this completely ignores how the Middle Ages contained Renaissances of its own, including the Carolingian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century.

- Gobi Desert (1292)

- Kublai Khan suggests that his father was Ögedei Khan, despite his actual father being Tolui.

- Several characters reference Marco Polo's Book of Marco Polo, including a merchant who gives Mario a few pages from it. However, Marco only wrote it after returning to Venice, while he was imprisoned with writer Rustichello da Pisa.[23]

- Also, they are insistent on its title being "Book of Marco Polo," but this is not the actual title of the book. It is Les voyages de Marco Polo[24] (The voyages of Marco Polo) or Le Devisement du Monde[25] (The Description of the World) in French, Il Milione (The Million) in Italian,[26] and The Travels of Marco Polo[24] in English. The closest name is an 1871 English translation by Henry Yule titled, The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East.[27]

- A sage claims that China had glasses when Europe did not, but this is incorrect: they were first documented in Italy in 1306,[28] while none of Marco Polo's writings reference them.[29]

- London (1595)

- The history pages suggest that Queen Elizabeth I's support is what allowed William Shakespeare to flourish. Although she watched some of his plays,[30] she was not a patron of his.

- Mainz (1455)

- Mario receives a Tea Bag from a librarian, despite tea bags first being created in the opening years of the 1900s and only being commercially available in the 1920s.[31]

- The same librarian says that Gutenberg loved to read books as a kid, but not much is actually known about Gutenberg's early life.[32]

- Menlo Park (1879)

- A hardware store clerk says that he has all of Thomas Edison's phonograph records, including "Mary Had a Little Lamb." While Edison did indeed test his invention with the poem,[33] this recording was not publicly available.

- A hotel owner mentions Edison's creation of an alkaline battery, which he only patented in 1904.[34]

- Orleans (1429)

- Joan of Arc's Shield depicts her coat of arms, but the game takes place during the siege on the Tourelles (which took place on May 7[35]) and her coat of arms was only granted to her on June 2.[36]

- Pacific Ocean (1521)

- Juan Sebastian Del Cano describes Ferdinand Magellan's wanderlust, and how he wants to travel the world simply for the sake of it. However, from the start, his intention was to discover a route to the Maluku Islands.[37]

- Also, the game spells his name as "Del Cano," which is a misspelling.[38]

- Mario gives a Telescope to Juan, despite them being first patented in 1608.[39]

- Mario receives a Rat Trap holding a spring-loaded bar from the ship's bosun, despite this being first patented in 1894.[40]

- Ferdinand suddenly decides to give the Strait of Magellan its name after an off-hand comment from Mario. However, he called it the "Estrecho de Todos los Santos" ("Channel of All Saints"), after All Saints' Day; his crew was the one who named the ship after their captain.[41][42]

- Philadelphia (1776)

- An innkeeper calls the American army the "Continental Forces" and not the Continental Army.

- Benjamin Franklin brings up Thomas Jefferson's Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which he drafted in 1777 and introduced in 1779.[43]

- Though the game depicts Thomas and the other Founding Fathers of the United States signing the Declaration of Independence on July 4, this event took place on August 2; July 4 was when Congress approved the document.[44]

- The history pages describe Thomas Jefferson's book collection as "the nucleus of the Library of Congress." This is slightly misleading: the Library of Congress was founded in 1800,[45] and he sold his personal collection to the library in 1812.[46]

- Stratford-upon-Avon (1601)

- Numerous characters quote lines from William Shakespeare's plays. For example, Anne Hathaway says "Is this a dagger I see before me, the handle toward my hand?" from Macbeth (believed to have been written in 1606[47]), and an unnamed man quotes "O brave new world, that has such people in't" from The Tempest (believed to have been written in 1611[48])

- The wording of many quotes also slightly differ from their sources, though this was most likely done to better integrate them into the dialogue.

- Richard Burbage claims that Shakespeare has written "some 24" plays; although certain sources line up with this statement,[49] it is generally difficult to precisely determine when each play was written.[50]

- An unnamed man in Stratford-upon-Avon brings up the theories that Shakespeare's plays were actually written by Francis Bacon or by Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. This is despite those theories first appearing in 1857[51] and 1920,[52] respectively.

- Vienna (1824)

- An innkeeper claims that Ludwig van Beethoven "threatened" to premiere his Ninth Symphony in Germany instead of Austria. This is slightly misleading: Beethoven considered performing in Berlin in response to (what he perceived to be) a decline in musical taste within Vienna, but in response, numerous Viennese citizens convinced him to stay while praising his talent.[53]

- The history pages claim that Ludwig gave his first concert at age eight, when he was actually seven.[54]

Reception

Since its release, Mario's Time Machine has received negative reception. It holds an aggregate score of 60.25% on Game Rankings based on two reviews. Nintendo Power gave it a 10.6 out of 20, while Electronic Gaming Monthly gave it a slightly better rating of 6.75 out of 10. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Good Game described it as one of many "awful" games that used the Super Mario license, and said that it was "too complicated" for its young target audience.[55] Similarly, authors David Wesley and Gloria Barczak include both it and Mario is Missing! in the "flood" of poor-quality 1990s Super Mario games and media made by third parties with no supervision from Nintendo, accusing these two games, Mario's FUNdamentals, and the Super Mario Bros. film of "nearly destroy[ing]" the entire franchise.[56] Patrick Felicia, who focuses on learning through video games, criticizes Mario's Time Machine and Mario is Missing! for their "mismatch" between the gameplay and the presentation, while also praising Super Mario Bros. due to everything being in service of platforming.[57]

| Reviews | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reviewer, Publication | Score | Comment |

| Steve Grant, SomethingAwful | -42/-50 | "Defining Moment: Beethoven telling me to "Go away." As always, I should have listened." |

| "The Cubist", Nerd Bacon | 5.5/10 | "In the end Mario's Time Machine is just another educational game as advertised, but it exceeded my expectations as such, if nothing else due to its strengths compared to Mario is Missing! and its relatively robust dissemination of historical information of note. Much like Mario is Missing!, this isn't really a game you'll need or even want to play, though it's a decent example of education done right, at least mostly so." |

| Nintendo Power | 10.6/20 | "Unlike Carmen Sandiego games, you don't have to know the subject to play the Game. You can actually learn a thing or two. [However,] Non-intuitive commands can make the game frustrating to control. Players expecting a traditional Super Mario game will not find it here." |

| Aggregators | ||

| Compiler | Platform / Score | |

| GameRankings | 60.25% | |

References to other games

- Super Mario World: Most of the music cues are direct arrangements of music cues from Super Mario World: for example, the title screen music is an arrangement of the Vanilla Dome theme which also incorporates the melody from Super Mario World's Castle theme. Most of the game's character sprites are also repurposed.

Gallery

- Main article: Gallery:Mario's Time Machine

Pre-release and unused content

In the first page of the instruction booklet, there is a very rough version of Bowser and his Koopas with the Timulator; the latter resembles the DOS version, although it is still a different design.

Media

| File info |

Staff

- Main article: List of Mario's Time Machine staff

References

- ^ February 1994. Total! issue 26. Future Publishing (British English). Page 44-45.

- ^ Mario's Time Machine SNES instruction booklet, page 1.

- ^ Anderson, Jaynie (December 1, 2003). Tiepolo's Cleopatra. Macmillan (English). ISBN 978-1876832445. Page 38–39.

- ^ Cantani, Arnaldo (December 17, 2007). Pediatric Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3540207689. Page 724.

- ^ Hankins, Justine (November 6, 2004). "That Sinking Feline". The Guardian. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Santangelo, Federico (December 17, 2007). "Warfare and Politics: Sulla in Italy" - Sulla, the Elites and the Empire: A Study of Roman Policies in Italy and the Greek East. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-9004163867. Page 68–69.

- ^ Arnold, Dorothea (1995). "49. Cobra on Pharaoh's Forehead" - An Egyptian Bestiary. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Page 43.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (1994). "Magic Figurines and Statues" - Magic in Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292765597. Page 103.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (1994). "Amulets" - Magic in Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292765597. Page 109.

- ^ Boeckh, August (1858-1884). "August Boeckh's gesammelte kleine Schriften. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig. Page 195.

- ^ Blits, Katherine C (1999). "Aristotle: Form, function, and comparative anatomy" - The Anatomical Record.

- ^ Reale, Giovanni; Catan, John R. (December 21, 1989). A History of Ancient Philosophy: The schools of the Imperial Age. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0791401293. Page 207-208.

- ^ Hall, Alfred Rupert (September 11, 1998). Philosophers at War: The Quarrel between Newton and Gottfried Leibniz. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521524896.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (1687). Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica - Jussu Societatis Regiae Ac Typis Josephi Streater. University of Cambridge Digital Library.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (September 19, 2017, 09:17pm ET). Halley's Comet: Facts About the Most Famous Comet. Space.com. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Lederman, Leon M.; Teresi, Dick (June 26, 2006). The God Particle: If the Universe Is the Answer, What Is the Question?. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0618711680. Page 100.

- ^ Hall, Alfred Rupert (September 11, 1998). Philosophers at War: The Quarrel between Newton and Gottfried Leibniz. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521524896. Page 10-11.

- ^ Ely, Margaret (September 24, 2013). History behind 'An Apple a Day'. The Washington Post, WP Company. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Clément, Charles (1880). Michelangelo. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. Page 8–9.

- ^ a b Johnson, Paul (August 6, 2002). The Renaissance: A Short History. Modern Library. ISBN 978-0812966190.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio; Foster, Jonathan (translator); Bohn, Henry G. (translator) (1850). "Michelangelo Buonarroti" - Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects: Translated from the Italian of Giorgio Vasari. ISBN 978-0375760365. Page 246.

- ^ "Renaissance Man". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (1998). "Marco Polo and His 'Travels'" - Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies Vol. 61, No. 1. Page 84–85.

- ^ a b "The Travels of Marco Polo" - WDL RSS. National Library of Sweden. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Florescu, Mihaela L. (August 20, 2014). "Marco Polo's Le Devisement Du Monde – Narrative Voice, Language and Diversity by Simon Gaunt (Review)" - Comitatus. Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA.

- ^ Polo, Marco; Pizzorusso, Valeria Bertolucci (editor) (1975). Il Milione Letteratura italiana Einaudi. Retrieved May 5, 2024. (Archived January 31, 2005, 04:45:34 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Yule, Henry (1871). The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian, Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Ilardi, Vincent (2007). American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871692597. Page 4–5.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1962). "Eye-Glasses and Spectacles" - Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology. Cambridge University Press. Page 118–119.

- ^ 2011. "Did Queen Elizabeth I or Any of the Monarchs of the Time See Any of the Tragedies or Comedies Staged at the Globe Theatre?". The Guardian, Guardian News and Media. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Begley, Sarah (September 3, 2015). The History of the Tea Bag. Time. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Wallau, Heinrich. Johann Gutenberg. The Catholic Encyclopedia, Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Stross, Randolph (June 23, 2010). The Incredible Talking Machine. TIME.com. Retrieved December 20, 2017. (Archived August 17, 2013, 09:09:40 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Edison, Thomas. Edison Storage Battery Co. Alkaline Battery. No. US 827297 A, 1904.

- ^ 1911. "Orleans" - The Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., vol. 20. Cambridge University Press. Page 287.

- ^ 2007. "Joan of Arc's Coat of Arms" - Maid of Heaven. Maid of Heaven Foundation. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ^ Guillemard, Francis Henry Hill (1891). "The Passage of the Strait" - The Life of Ferdinand Magellan and the First Circumnavigation of the Globe: 1480-1521. George Phillip & Son. Page 67, 82, 93, and 102.

- ^ Múgica, S.. Elcano y No Cano (PDF). Euskomedia.org.

- ^ Helden, Albert von (1995). "The Telescope". The Galileo Project.

- ^ Hooker, William C. Animal-trap. No. US 827297 A, Nov 6, 1894.

- ^ Guillemard, Francis Henry Hill (1891). "The Passage of the Strait" - The Life of Ferdinand Magellan and the First Circumnavigation of the Globe: 1480-1521. George Phillip & Son. Page 213-214.

- ^ Murphy, Patrick J.; Coye, Ray W. (March 19, 2013). "Magellan" - Mutiny and Its Bounty: Leadership Lessons from the Age of Discovery. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300170283. Page 63.

- ^ "Act for Establishing Religious Freedom" - Education from LVA. Library of Virginia. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Bomboy, Scott (August 2, 2017). "On This Day, the Declaration of Independence Is Officially Signed". National Constitution Center. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ 2006. "The Library of Congress, 1800-1992" - Jefferson's Legacy. Library of Congress. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ September 3, 2007. Thomas Jefferson. LibraryThing. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ 2014. Macbeth: Background. BBC.com. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Bevington, David (April 26, 2017). The Tempest. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1930). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems, 1st ed., vol. 1. Oxford University. Page 270–271.

- ^ Wikipedia contributors (December 16, 2017). "Romeo and Juliet", "Date and time" section. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Bacon, Delia (1857). The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakspeare Unfolded. Groombridge and Sons, London.

- ^ Looney, J. Thomas (1920). "Shakespeare" identified in Edward De Vere, the seventeenth earl of Oxford. C. Palmer, London.

- ^ Sachs, Harvey (June 15, 2010). "A Grand Symphony with Many Voices" - The Ninth: Beethoven and the World in 1824. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1400060771. Page 29–32.

- ^ Thayer, Alexander Wheelock; Krehbiel, Henry Edward. "Paucity of Intellectual Training" - The Life of Ludwig Van Beethoven. The Beethoven Association.

- ^ May 11, 2009. "Edutainment" - Good Game. ABC. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ Wesley, David T. A.; Barczak, Gloria (June 28, 2010). "Nintendo's Dark Ages" - Innovation and Marketing in the Video Game Industry: Avoiding the Performance Trap. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0566091674. Page 40.

- ^ Felicia, Patrick (January 31, 2011). "Matching Basic (Cognitive) Activities" - Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Information Science Reference. ISBN 978-1609604950. Page 334.