Philips CD-i

| Philips CD-i | |

|---|---|

The Philips CD-i model CDi-220 | |

| Generation | Fourth generation |

| Release date | |

| Discontinued | 1998[3] |

| Predecessor | None |

| Successor | None |

The Philips CD-i (short for "Philips Compact Disc-Interactive") is a multimedia CD player developed by Royal Philips Electronics and released in North America, Europe, and Japan. At the time of its inception, the CD-i was not envisioned as a game console, being designed for general multimedia purposes based around various capabilities of the compact disc format (including music, home video, computing, and educational services); the inclusion of video game support was by comparison an afterthought. Despite this, however, it primarily maintains a reputation as a video game console, in part because of the near-unanimous negative reception towards many of its most prominent titles, including ones based around Nintendo's IPs. The CD-i was originally released in 1991 at the price of $700 in the United States, and it was released in both Japan and Europe the following year; releasing nine days before the Japanese launch of the competing Mega-CD (later released in the US as the Sega CD), it was the second video game system to support CD-based games, following the 1988 launch of the PC Engine CD-ROM² (later released internationally as the TurboGrafx-CD). Atypically, CD-i games were not released on CD-ROM discs but on an eponymous bespoke compact disc format (alternatively known as the Green Book standard).

Nintendo originally made a deal with Philips to develop an add-on for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System to allow it to play CD-based games, after a similar deal with Sony had fallen through. The project was later aborted, but in exchange for Philips' involvement, Philips was given the license to use five of Nintendo's characters in games.[4]

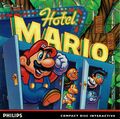

Using Nintendo's licenses, Philips released three games for the series The Legend of Zelda, one for the Super Mario franchise (two more were planned but were canceled), and a version of Tetris. The games of The Legend of Zelda and of the Super Mario franchise received very bad reception, and the system generally sold poorly after 1994. Common criticisms of the CD-i were its price, the graphical quality of its games (compared to the Super Nintendo or Sega Genesis), its poor library of games (including an influx of point and click games, pornographic games, and educational games), and the controls. Special criticism was used for the controllers of the CD-i. There were four main models of the controllers of the CD-i: a basic controller with three buttons and a D-pad (the console used only two buttons; the third was mapped to the first two buttons being pressed simultaneously), another that resembled a spoon, another similar to the first one but with a protruding stick on top, and one resembling a TV remote, which was the one that came standard with all the consoles. Also in the vein of a remote control, the latter was wireless, communicating with the CD-i using an infrared sensor; because a connection between the infrared ports had to be continuously maintained, moving the controller out of alignment or placing another object between it and the console would cause it to become nonfunctional until the connection is restored. None of the controllers featured a Start button.

In 1998, Philips announced that the CD-i had been discontinued, following low consumer adoption caused by a combination of its high price point, unreliable controls, poor video game library, and pressure from competing devices in every field it tried to tap into, both within and outside video game-related niches.

Super Mario games

- Super Mario's Wacky Worlds (canceled)

- Mario Takes America (canceled)

Unannounced Donkey Kong title

A Donkey Kong game was apparently in development for the system. His character was announced for an appearance in the console in a 1991 advert.[5] The only known report of it is the LinkedIn resume of programmer Adrian Jackson-Jones, which states the game was in development during the 1992–1993 period at Riedel Software Productions. Jackson-Jones "designed and implemented the game engine" for the project.[6] In an interview with Time Extension, Jackson-Jones stated that due to a memory disorder, he recalled little of the production process other than programming the game; however, he was able to confirm his involvement with it, stating that the game had to circumvent the CD-i's memory limitations by only loading in what would be visible on-screen based on the player's movement.[7] A later interview between video game trivia YouTubers DidYouKnowGaming and an anonymous Riedel Software Productions artist further revealed that the game was planned to be a side-scroller like the later Donkey Kong Country series and that development never made it past storyboarding due to the CD-i's technical limitations and Philips' inexperience with game development.[8]

References

- ^ Nicolas Robillard. CD-i by Philips. Video Game Kraken (English). Retrieved January 31, 2025. (Archived September 15, 2024, 01:05:10 UTC via Wayback Machine.)

- ^ Bas (July 7, 2007). "CD-i in Japan - Philips Artspace and Japan Interactive Media". Blogger. Archived June 13, 2012, 03:52:15 UTC from the original via Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 28, 2024.

- ^ Blake Snow (May 4, 2007). The 10 Worst-Selling Consoles of All Time. GamePro. Page 2. Archived May 8, 2007, 03:58:15 UTC from the original via Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Shona (March 28, 2013). An interview with the creator of the CD-i Zelda games. Zelda Universe. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ 1991 advert.

- ^ December 13, 2010. RSP say they worked on Donkey Kong on CD-i. Interactive Dreams. Archived July 18, 2019, 10:51:26 UTC from the original via Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Szczepaniak, John (July 29, 2023). Like Zelda And Mario, Donkey Kong Was Supposed To Get A Philips CD-i Game - What Happened?. Time Extension (English). Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ DidYouKnowGaming (May 12, 2024). Rumored Mario Games SOLVED. YouTube. Retrieved May 12, 2024.