The 'Shroom:Issue LXVI/A History of Video Games

Hell-o everyone, it is Toad85 again, with another exciting edition of “A History of Video Games”

We’ve finally hit 1989. Ah, that swinging time of post-Berlin Wall culture. George H.W. Bush becomes President, Tiny Tim runs for mayor of New York, movies include Field of Dreams, Glory, and Ghostbusters II, and most internet celebrities are kids.

But in the Video Game world, Sega is looking for another shot to take down Nintendo. Like Little Mac in the corner, Sega plans on how to take the title… wait bad example, that’s a Nintendo game. How about Sega being like Olimar, picking up the pellets of their failed ideas and using them to make a brand new Pikmin colony… wait, that’s another Nintendo game. Okay, Sega’s more like the lone Mii in the plaza that no one wants to buy fro… DOGGAMNIT WHY CAN’T I MAKE AN ANALOGY THAT DOESN’T INVOLVE A NINTENDO GAME.

You get the idea. Sega’s the underdog, Nintendo’s the overdog, they go head to head in ’89. No analogy need be made.

PLAY THE ARTICLE.

CONSOLE WARS EPISODE II: ATTACK OF THE BITS

So Sega’s far from being in the toilet, but they’re far from making a dent in the console market. Well they kind of did in the PAL region, but Sega didn’t give a flying feather about them.

Sega had always employed its maxim “if at first you don’t succeed, throw more stuff at ‘em”. But now, the timing was right for another attack. After 4 years of being on the American market, and 6 years in Japan, the NES’s dominance was finally beginning to crack. A steady stream of quality titles wasn’t enough to satisfy American or Japanese audiences. They wanted more; a new console that could be a worthy successor to the now-outdated NES. However, Nintendo was sitting pretty on their hefty profit, and weren’t in any hurry to make a 16-bit console anytime soon. With this gap in the industry that needed filling, a few companies were making jumps to satisfy gamer’s need for faster, better-looking, and more advanced gaming experiences.

The first companies to bring a next-generation console to market were NEC and Hudson Soft. Their collaboration project, the Turbografx 16, had gone to market in Japan in 1987. Though it didn’t have full 16-bit processing capabilities, it certainly looked the part with beautiful graphics and crisper gameplay than the majority games on the NES. Hudson was planning on bringing the console to the U.S.A. late into 1989, which left SEGA with some valuable time to bang out its own machine, which would be dubbed the “Mega Drive”.

Unlike former NES developers like NEC and Hudson, Sega had experience dealing with 16-bit technology via their arcade exploits. The Mega Drive would be a compilation of all the developers knowledge of the tech put together into one box. The Mega Drive went to market in time for Japan’s holiday season in 1988, and while its first year was a flop, 1989 led to Sega’s first moderate success in the console market: 400,000 units sold. Hayao Nakayama, who was directing Mega Drive production, invigorated his employees with the phrase “Hyaku Mankai!”, which means “One million times!” in English. Nakayama’s goal was to sell 1,000,000 Mega Drives the next year, and at the rate Sega’s place in the market was growing, it wasn’t out of the question.

With success in Japan, Sega was ready to launch the system in America, with the new Christian-friendly name “Genesis”, pack-in game Altered Beast, and new President of Sega of America Michael Kratz. However, when the Genesis hit American shores, there were three big problems that had to be addressed.

First of all was a lack of third-party developers. Pretty much everyone at the time was either under Nintendo’s direct control, making their own console, or not giving a crap about the console market. So Sega’s in-house developers, as they had with the Master System, had to fire on all cylinders and bang out as many quality games as possible. Instead of using well-trusted third-party brand names like “Mega Man” or “Castlevania”, Sega relied on the purchasing power of celebrities from King of Pop Michael Jackson to Hall of Fame baseball manager Tommy Lasorda.

Second, Sega had an awry advertising budget. Aside from being pitifully small, what few ads did run only said “Brings the arcade experience home!” Which, of course, only spoke to those gamers that still played arcade games, and not to those looking for a new console to replace their busted-up Famicom. Kratz devised a strategy to not only get more orders for the Genesis, but also drive down Nintendo’s sales. The advertising budget skyrocketed, and Genesi (Geneses? Genesises?) were proudly splashed across magazines and television screens. Ads proclaimed the glory of “blast processing”, and claimed that the Genesis "did what Nintendidn’t".

But not even crazy commercials could bring up sales, and Nakayama’s dream of “Hyaku Mankai!” was fading fast. What Sega was missing quickly came to light: a true mascot. Okay, there was Alex Kidd, and sure, there was Altered Beast, but Sega didn’t really have a singular character to rally behind. Meanwhile, their main competition each had their own cartoon character that brought in the big bucks: Nintendo had Mario, and Hudson had Bonk. In order to really succeed as a brand, Sega needed its own Mario.

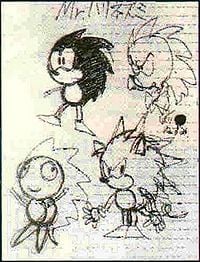

So what did they do to rectify this severe breach in their game market? Why, they hold a competition! Sega held an in-house contest to see what new character should take the slot of Sega’s new mascot. Some of the 200 nominees included an armadillo, a bunny rabbit that could use its ears to throw objects, and an overweight Teddy Roosevelt in pajamas. But the winner was a design submitted by Naoto Oshima. Oshima, who hours before had shouted “DRUNK ARTWORK!” and downed a case of beer, held in his hand a scribble of a hedgehog character who was supposed to run faster than the speed of sound. Obviously, Hayao “Hyaku Mankai!” Nakayama loved the idea. And so “Mr. Needlemouse” was born.

Unfortunately, just about everyone else in the company believed that “Mr. Needlemouse” was a stupid name. So he was rechristened “Sonic” and given a blue paintjob to match the Sega logo. That ought to appease everyone, right?

So Oshima was teamed up with budding programmer Yuji Naka and his “Sonic Team”, and work on the first Sonic game commenced. Inspired by none other than the plumber in red himself, Naka crafted a game that could be easily described as “Mario on amphetamines”. With fast gameplay, tight jumps, and rigorous platforming, Sonic the Hedgehog was one of the fastest-paced games of its time.

And not only was it fast, it had attitude. Sonic was harder than any released Mario game at that time (unless you’re one of the unlucky Japanese players who got Lost Levels), and Sega planned to play it up. The hedgehog was designed with Michael Jackson’s rebellious style and Bill Clinton’s assertiveness. Sega, with Sonic’s leadership, was to be the older kid’s alternative to Nintendo. Sonic was in-style. Cool. Hip. Mario was old news. 80’s stuff. Boredom in 8-bit form.

But when Sega tested the game in the States, they got a little feedback that wasn’t so positive. The most easily seen issue was the artwork. The 90’s was not like now, where Anime is growing in popularity around the world and you’ve got guys like User:Uniju :D espousing its wonders. Twenty years ago, depending on how close you were to a metropolitan area, Japanese cartoons were either completely unheard of or totally unwanted. Also, Sonic was a monkey-fighting hedgehog. I doubt anyone in America at the time had ever even heard of one.

So Sega of Japan, in response, did some pretty ridiculous stuff, such as putting Sonic in a rock band and giving him a human girlfriend not named Elise. When Sega of America heard of all this crap going around, they just said something to the effect of “screw it, just hand over the rodent to us. We know what the heck we’re doing.” Marilyn Schroeder, one of Sega of America’s directors, was put in charge of Americanizing Sonic. The rock band and human girlfriend were the first things to go. Then the Anime artwork; Sonic was given a more “western” feel. She also softened up Sonic’s hardcore personality a bit, to make him more accessible (read: marketable) to kids of all ages. Sega of Japan was a bit pissed, but they trusted Schroeder would pull their mascot through.

Sonic the Hedgehog was released officially on June 23, 1991, to mild success. However, Sega needed a bigger dent in the video game market to compete with the NES, and Sonic alone wasn’t cutting it.

And here’s where Tom Kalinske came in. Formerly head of Mattel, Kalinske had recently saved the Barbie toy line almost single-handedly. He was hired as President of Sega of America in 1990, and he wanted a say in Sonic. Much like the North in the American Civil War, Kalinske utilized a three-part plan to push Sega, and particularly the new Sonic franchise, into the lead:

- 1 – Sega was going to lower the price of the Genesis from US$199 to US$149. This way, Sega could reach some of their more stingy customers, as well as undercut Nintendo’s prices.

- 2 – Move the development for future Sonic sequels to North America. Since Sega was primarily targeting the States, Kalinske thought it best to have the company’s flagship series developed by people who knew what American tastes were like.

- 3 – Bundle the Genesis with Sonic the Hedgehog instead of Altered Beast.

This plan, especially the last part, was not particularly welcomed in Japan. Sega was relying on Sonic sales to boost the company; they weren’t going to just give away their biggest seller for free! And if you’re selling a free Sonic game, why also cut the console’s price?

Kalinske’s idea, though, was that if consumers would get a free game with their console, and pay less while they were at it, Sega’s boosted console sales would bring in any profit lost from giving the free game in the first place. Reluctantly, Sega complied with Kalinske’s plan in time for the 1992 market.

And boy did it work. Sega’s share in the market shot up to a record high of 55%, and Sonic had topped Mario as the franchise to beat. In a matter of a year, Sonic had gone from being “DRUNK ARTWORK!” to a merchandising phenomenon. Additionally, as a result of increased Genesis sales, Sega was selling more software than ever before. In 1992, Sonic got a sequel, and subsequently went viral everywhere from America to Japan to New Zealand. But would Nintendo take this sitting down?

Alright, thanks again to User:Lily for the artwork at the top of the page. Thanks to the readers for being literate. Also, thanks to my high school for allowing me to catch up on writing this and having teachers that don’t give a darn what site I’m on. And thanks to TomSka for not suing me for stealing your joke. You’re the best.

This is Toad85 signing out, and that’s the way it was.