The 'Shroom:Issue LXII/A History of Video Games: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (Text replacement - "class="shroom(winter|spring|summer|fall)"" to "class="shroombg shroom$1"") |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOEDITSECTION__ __NOTOC__ <noinclude><div class="shroomspring"></noinclude><div class="right"><h2 style="font-family:Kunstler Script;font-size:350%;color:black">A History of Video Games</h2> | __NOEDITSECTION__ __NOTOC__ <noinclude><div class="shroombg shroomspring"></noinclude><div class="right"><h2 style="font-family:Kunstler Script;font-size:350%;color:black">A History of Video Games</h2> | ||

by {{user|Toad85}}</div> | by {{user|Toad85}}</div> | ||

Latest revision as of 22:29, June 18, 2023

Hello, it’s Toad85 again, with my seventh edition of “A History of Video Games.”

Cutting to the chase, it is now 1982. Nintendo’s Donkey Kong was taking the video game world by storm. There were licensed products, ranging from a breakfast cereal to a board game. Yes, a board game. Despite all this success, though, Nintendo was still a small company. And this year, the year after they finally made a big dent in the gaming market, they were forced to go up against Universal City Studios over a trademark dispute.

This, my friends, is Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

(*theme song*)

PART FOUR: THE LAWSUIT OF THE DECADE

In 1982, as I just said in the above blurb, Donkey Kong was the must-play game of the year. It was the bomb. Or should I say it was the bob-omb? Screw it, Toad, move on with the article.

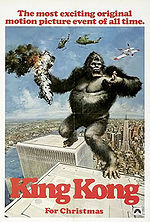

Anyway, this company called Tiger Electronics (You know, the makers of those crappy LED handheld games you find at Target?) wanted to produce their own hit. Seeing how much of a bob-omb Donkey Kong was, wanted to cash in on its success. They developed a rip-off game, entitled King Kong, and went to Universal City Studios to get the rights. Universal did a background report on King Kong, finding little other than an old license with a costume-making company, and granted Tiger the rights.

However, when Universal did a second background report, and discovered Donkey Kong. Nintendo and a hardware company called Coleco were negotiating the terms of a port of Donkey Kong for Coleco’s new console. President of Universal Sid Sheinberg, wanting to cash in on the video game market, devised a plan to break into the market. First, he voided the Tiger deal, because profits from it were way too low. Sheinberg then confronted Coleco president Arnold Greenberg on April 27th, ordering that Coleco cease negotiations with Nintendo and give them a cut of Donkey Kong’s profits. If Greenberg complied, Sheinberg offered future business ventures. This was bad news for Greenberg’s console, for it was about to ship in a few weeks, packaged with Donkey Kong, but Coleco agreed to the terms anyway. To top it all off, Sheinberg declared that Nintendo’s hit game infringed on their copyright of King Kong, and wanted Nintendo to pay for it.

Nintendo responded by requesting a meeting to discuss the trademark issue. Representing Nintendo were Nintendo of America head Minoru Arakawa and lawyer Howard Lincoln. Universal’s lawyer demanded that Nintendo pay for their copyright infringement, and sought royalties from Donkey Kong. Lincoln responded to this with the immortal line “We’re not going to buy the Brooklyn Bridge.”

For those of you that don’t know, “buying the Brooklyn Bridge” means accepting or paying for something gullibly or foolishly, such as buying the Brooklyn Bridge. It’s a public bridge, maintained and operated by the NYC Department of Transportation. No one owns it. So no one really can sell it to you. Buying the Brooklyn Bridge from someone, even Mayor Bloomberg, would be absolutely silly.

Lincoln was dead-set in his belief that Nintendo wouldn’t fall easily for Universal’s offer of what was essentially the Brooklyn Bridge. In fact, Lincoln claimed that Universal couldn’t be making their copyright infringement contentions in the first place. Lincoln ran his own copyright back-check of King Kong, and found many unlicensed uses of the gorilla that had seen no qualms from Universal. So why the heck should Nintendo (who wasn’t even using King Kong’s name) be any different? Universal said that they had a chain of title that would prove Lincoln wrong, but never sent it. On May 21st, Nintendo officially announced to Sheinberg that he would not acquiesce to Universal’s demands.

Reportedly, Sid Sheinberg went ballistic, and the Sheinberg officially sued Nintendo (and some other companies that had made Donkey Kong products) on June 29th. Nintendo had entered a battle with a Goliath, and they weren’t likely to come back out alive. But they did, did they not? That’s why this website is able to exist, right? Here’s how:

Howard Lincoln hired John Kirby, a fellow lawyer, to represent Nintendo in the case. His disheveled attitude struck Lincoln as peculiar, but boy was he a lawyer. Insert lawyer joke here.

In all seriousness, Lincoln really couldn’t have picked a better guy for the job. Kirby was already famous for defending PepsiCo. in anti-trust cases, and had worked with General Foods and Warner-Lambert. Kirby was happy to receive the role, and quickly flew to Japan to meet with President Hiroshi Yamauchi (remember him?). Kirby researched the game’s development, including interviewing Gunpei Yokoi and Shigeru Miyamoto. Miyamoto said that he had in fact called the ape in Donkey Kong “King Kong,” during development, but had no intention of naming the character that. In Japan, “King Kong” was a generic term for any large ape. Kirby and Lincoln headed back to the ‘States for the first day of trial, expecting to put up a good fight, even if they were to lose.

But then came the discovery that changed everything.

You see, Universal City Studios had recently gone to court with RKO Studios in a similar case. However, Universal in that case had gone yards to prove that King Kong wasn’t their intellectual property, in order to publish Dino De Laurentiis’s remake. If Universal didn’t own King Kong, how could they expect Nintendo to pay royalties? Also, Lincoln and Kirby had unearthed documents proving Universal’s connection to Coleco, as well as Universal’s desire to enter the video gaming industry. Lincoln’s suspicions were right! Nintendo had done nothing wrong! Once the court saw this evidence, Nintendo would be home clear!

With Judge Robert W. Sweet presiding, Universal and Nintendo finally entered court. Nintendo stuck by their defense, even having one of their employees play Donkey Kong in front of the jury, to prove there was no similarity between the game and King Kong. Kirby also brought up the old court cases where Universal had proven that King Kong belonged in the public domain, not that they owned it, and mentioned that Sheinberg had mentioned that he viewed litigation as a profit center.

Sweet’s jury had no problem deciding upon the verdict. He made the following points:

- Universal did not own the rights to King Kong

- Because they did not own the rights to King Kong, they could not sue Nintendo for copyright infringement.

- Nintendo, even if Universal did have the copyright, would not have infringed upon anything by publishing the game, because people would not confuse the menacing King Kong for the lovable DK. Donkey Kong was a parody of King Kong at most, and completely unrelated at least.

- Universal was ordered to pay Nintendo $1,800,000 in damages, and to return the money they had taken from other companies that had made Donkey Kong products. That’s about $4,012,000 today.

Universal would appeal this case multiple times, of course being the sore losers they were, but failed to go anywhere with it.

This was a monumental case for several reasons. First of all, Nintendo set for the record that they were not going to be fooled with. They were firmly planted in the Americas, and wouldn’t be pushed around by bigger companies like Universal. Nintendo’s victory was a victory not only for itself, but for many small companies around the world who might fall into legal issues in the near future. Hey, if Nintendo can do it, you can too!

So where are they now?

Howard Lincoln, for his efforts, would be promoted to Chairman of Nintendo of America, and would remain there for a long time. After leaving, he became Chairman of the Seattle Mariners (which is owned by Nintendo. What a coincidence, right?)

John Kirby got a sailboat named “Donkey Kong” from Nintendo, as well as exclusive rights to use the name for boats. He is also probably the inspiration for the HAL Laboratories character Kirby, though Kirby’s creator Masahiro Sakurai has been quoted saying he does not remember if that was the case or not.

Colecovision would eventually go on to sell their console. It did fairly well, but the Video Game Crash of 1983 took a huge bite out of the company. It soon left the industry for good, and closed its doors in 1989.

Universal? Well, they didn’t forget about their dreams of owning their own video game company. Soon after, Universal would buy a little toy and gaming company called LJN.

Yes, that LJN. Thank you, Universal, for ruining James Rofle’s life.

Sheinberg started a production company in 1995 when Seagram bought Universal, and produced a string of bad movies.

And Nintendo? Well, take a look at how many of their games you own to tell where they went.

I’m Toad85, your local video game historian, and that’s the way it was.